Sleeving an engine means inserting a cylindrical liner into a worn cylinder bore to create a fresh, durable surface for the piston to ride against. This repair technique rejuvenates tired or damaged cylinders without replacing the entire engine block, making it especially relevant for motorcycles, cars, and larger industrial builds where downtime and cost matter. Sleeves can extend engine life after bore wear, scoring, or heat-related damage and are common in both performance restorations and routine rebuilds. The choice of sleeve type and installation method affects heat transfer, coolant interaction, and long-term reliability, so understanding the mechanics helps owners, distributors, and repair shops make informed decisions. This article unfolds the topic in three focused parts: (1) the purpose and mechanism behind sleeving, (2) a compare-and-contrast of dry sleeves versus wet sleeves and how coolant interacts with the liner, and (3) the economic and practical considerations that shape whether sleeving is the right call for a given engine project. With these insights, motorcycle and auto owners can assess options with confidence, distributors can size inventory for common bore geometries, and shops can estimate tooling, turnaround, and serviceability while keeping customers informed and expectations clear.

Between Block and Bore: The Purpose, Mechanism, and Practical Realities of Engine Sleeving

Engine sleeving is quieter than it sounds, but its impact reverberates through the heart of an engine. It is not merely a repair trick or a stopgap fix; it is a carefully engineered restoration that preserves a block, restores precision, and sometimes quietly enables a different kind of performance. When sleeves are fitted into a worn or damaged cylinder bore, the piston now interacts with a fresh, consistent inner surface. The process can be applied to a wide range of engines, but it is especially common in diesel and high‑performance builds where wear, heat, and loading stress have carved deviations into the bore that cannot be ignored. The result is a bore that behaves like new, or at least like a new one of a larger or tailored size, depending on the goals of the rebuild. Understanding sleeving requires looking at two intertwined aspects: why sleeving is chosen, and how the sleeve is captured inside the block so that it becomes a durable, thermally managed, and mechanically stable part of the engine.

To begin with the purpose, sleeving is a response to a genuine mismatch between the piston’s movement and the cylinder’s condition. Worn, scored, or out-of-round bores create friction, reduce compression, and distort the seal formed by piston rings. In older engines, where the block is valuable or scarce, or in engines that operate under demanding conditions, replacing the entire block is not always practical or affordable. Sleeving provides a cost-effective route to restore the cylinder’s inner diameter to a precise standard without the expense and scale of a block replacement. In many cases, this is the most economical way to salvage an engine with relatively few other issues.

But the purpose goes beyond mere restoration. A sleeve can be made from a material that is harder or more wear-resistant than the original bore, which can improve durability under high loads, elevated temperatures, or aggressive fuel or oil choices. This enhancement is one of sleeving’s subtle strengths: it allows engineers to choose a bore surface that better suits the engine’s operating envelope. For high-performance applications, sleeves can be paired with precisely sized pistons to tune compression, displacement, or ring seal behavior while preserving the block’s core geometry. Sleeving also enables customization without sacrificing the existing engine’s core. If a vehicle or machine has historic value, rarity, or a signature block, sleeving makes it possible to refresh the cylinder experience without erasing the block’s provenance.

In practical terms, sleeving is frequently part of a larger engine rebuild. It sits alongside crankshaft work, valve trains, and piston assemblies, each of which relies on a correctly prepared cylinder to deliver uniform compression and reliable ring seal. The process is iterative: technicians assess wear patterns, decide on the sleeve fit, machine the bore to create an optimal seat, and then install and finish the sleeve so that the final bore meets exacting tolerances. The outer surface of the sleeve must be supported by the block material; without proper support, a sleeve can move, crack, or become misaligned under heat and pressure. This interplay—an inner wear‑surface that has to stay perfectly round and concentric, surrounded by an outer shell that must not deform under combustion heat—defines sleeving as both art and science.

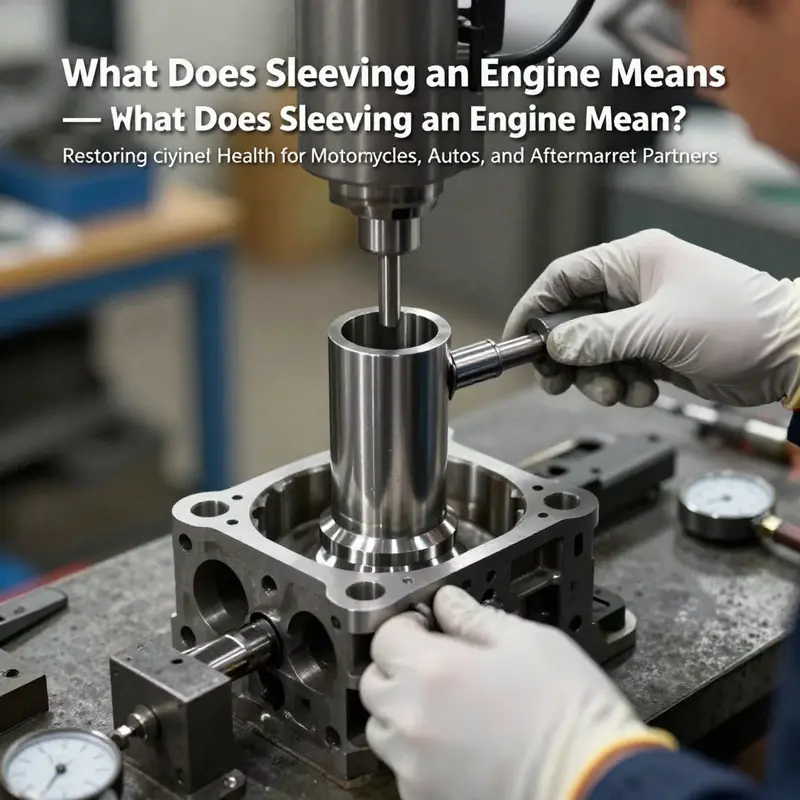

The mechanism by which the sleeve becomes an enduring part of the engine is a sequence of precision steps, each requiring careful control of dimensions, fit, and material behavior. The bore is first prepared: the damaged or worn area is removed with milling and honing to establish a clean, round interface. The sleeve itself, typically a cylindrical liner of cast iron or steel, is then prepared for insertion. There are two broad installation philosophies, each with its own technical nuances. In a press‑fit or interference‑fit method, the sleeve is slightly oversized relative to the bore and is pressed into place with a calibrated force. The outer diameter of the sleeve and the inner diameter of the bore are matched so that, once seated, the sleeve clamps itself to the block, resisting movement under thermal and mechanical stress. In shrink‑fit or thermal expansion methods, the sleeve is cooled so that it contracts, or the bore is heated, so that the sleeve can slide in. As the temperature equalizes, the sleeve expands to form a tight seal with the block walls. In either case, the goal is the same: a precise, stable interface that endures the heat, pressure, and motion of billions of strokes.

The choice between dry sleeves and wet sleeves adds another layer of complexity, and the decision hinges on cooling strategy and the engine’s design philosophy. Wet sleeves place the inner surface in direct contact with the coolant. This arrangement requires seals and careful sealing at the top and bottom of the sleeve to prevent leakage and to maintain effective heat transfer from the bore to the cooling system. Wet sleeves can provide superior heat management for demanding engines, because the coolant can directly withdraw heat from the liner itself. However, they demand higher precision in the sealing interfaces and in the mating geometry between sleeve, block, and head. Dry sleeves, on the other hand, rely on the surrounding block material to carry heat away and to provide structural support without exposing the liner to coolant. Dry sleeves can simplify sealing concerns and may be preferable in engines where coolant leakage is particularly problematic or where the block’s geometry provides excellent thermal paths. Both approaches share the same core objective: create a new surface on which the piston rings can ride with minimal blow‑by and optimal compression.

A closer look at the sleeve material underscores why sleeving can be more than a simple replacement. Cast iron and steel are common choices, each offering a different balance of machinability, wear resistance, and compatibility with the piston rings. Cast iron liners have excellent wear characteristics and a natural tendency to retain a mirror‑like bore finish after honing. They also interact with aluminum blocks in a way that supports rapid heat transfer and reduced thermal mismatch when properly engineered. Steel sleeves provide stiffness and can be engineered for specific bore diameters or surface textures that support high‑load, high‑speed operation. In some high‑end restorations, a sleeve may be selected to accommodate a larger bore diameter, enabling a tuned displacement without altering the block’s exterior geometry. This kind of bore customization is one of sleeving’s most powerful capabilities: you can preserve a cherished block while adjusting its internal geometry to your performance objectives.

The process itself—why and how the sleeve is inserted—illustrates the synergy between machining precision and material behavior. After the bore is prepared, a sleeve is chosen for its outer diameter tolerance and its compatibility with the block’s cooling strategy. The sleeve’s outer surface must fit the bore precisely; too tight, and it may stress the block during installation or operation. Too loose, and it can shift, seal poorly, or fail under the mechanical loads of combustion. The assembly is then secured by interference fit, and in many cases, the sleeve is subsequently honed to achieve a precisely round inner bore. This honing creates the cross‑hatch pattern that helps retain oil and lubricants, ensuring consistent ring sealing and efficient piston movement. The outer interface—the sleeve’s contact with the block walls—must be continuous and robust, so the sleeve remains stationary during thermal cycles and under the vibrations of engine operation.

In the final stages, attention turns to the alignment and sealing where the sleeve meets the cylinder head and the crankcase. The top and bottom must be sealed or backed by adequate collars so that coolant or oil does not find its way into unintended gaps. The piston rings seal the space between the piston and bore, and any misalignment or lack of concentricity translates directly into reduced efficiency and increased wear. This step emphasizes one of sleeving’s essential truths: the sleeve is not just a new surface; it is the core around which a broader system of seals, lubricants, and cooling flows is built. The outer sleeve surface must be supported, and the engine block must provide a stable thermal path to the rest of the engine. If the sleeve moves even a small amount during operation, the bore becomes non‑uniform, the rings lose their seal, and the engine’s compression and efficiency suffer.

The discussion of sleeves would be incomplete without recognizing the role of customization that sleeving enables. Because sleeves allow the bore to be rebuilt to standard dimensions or to a new, larger bore, they enable displacement changes that would be impractical with a worn block. This aspect is especially valuable in older engines that carry significant historical or monetary value. A block that might otherwise be discarded can be revived and reconfigured to meet contemporary performance or efficiency goals, all while preserving the essence of the original machine. It is this blend of preservation and modernization that makes sleeving a compelling option for engine builders who value both heritage and performance.

Of course, sleeving is not without its caveats. The process demands a high degree of precision and a thorough understanding of material behavior under thermal and mechanical stress. If the bore is over‑machined or if the sleeve’s outer diameter is misjudged, the resulting interference fit may either induce distortion in the block or fail to secure the sleeve properly during heat cycles. The choice between wet and dry sleeves influences sealing strategies, cooling efficiency, and long‑term reliability. Any deviation from the required tolerances can create a cascade of issues: oil leaks, coolant leakage, poor piston ring seal, accelerated wear, or even a sleeve that wobbles under load. For these reasons, sleeving is typically performed by technicians with access to precise measuring equipment, high‑quality machining centers, and an environment that supports meticulous quality control.

The practical realities of sleeving extend into the lifecycle of the rebuilt engine. After sleeving, the engine is typically reassembled with pistons that match the new bore size, and the rings are chosen to complement the final cross‑hatch pattern created by honing. The engine goes through a break‑in period during which the sleeve surface and the piston rings establish a stable oil film and a robust seal. Maintenance intervals may be adjusted to monitor for any sign of distress in the cylinder lining or cooling system. The sleeve’s long‑term performance depends on consistent lubrication, effective cooling, and careful heat management, all of which rely on a block that remains structurally sound and a cooling system that can carry away the heat produced during operation.

The broader lesson of sleeving, then, is that it is a disciplined balance between preserving a block’s value and accommodating a new internal geometry that aligns with modern demands. It requires a thoughtful choice of sleeve material, a precise installation method, and careful finishing to ensure that the inner bore, the outer block interface, and the cooling pathways work in harmony. When done correctly, sleeving can deliver a durable, reliable cylinder surface that supports efficient compression and smooth piston motion for many thousands of revolutions. When done poorly, it can magnify wear, create leakage, or produce thermal imbalances that undermine the engine’s integrity. The key is to respect the physics of heat, pressure, and expansion while applying the craftsmanship required to achieve a precise, stable, and durable bore.

For readers who want to dig deeper into the fundamentals and nuances of engine sleeving, there are authoritative resources that explain the technique in greater detail and with technical depth. For an overview of what constitutes an engine sleeve and how the surface interactions influence performance, see What are engine sleeves?. This primer helps connect the practical steps described here with the broader design decisions that guide sleeve selection and installation. In addition, if you seek broader context on sleeving cylinder blocks and related systems, consult industry literature that discusses cylinder liner systems and the interplay between block design, sleeves, and cooling. The technical landscape is nuanced, and the best outcomes come from aligning a sleeve choice with the engine’s operating demands, the block’s mechanical strength, and the precision capabilities of the shop performing the work.

External resources can illuminate the theory behind the practice. For a detailed technical treatment on sleeving cylinder blocks, see this external resource on engine sleeving and cylinder liner systems. It provides in‑depth discussion of the material choices, fit tolerances, and sealing strategies that underpin successful sleeving projects. Sleev ing cylinder blocks – external technical reference

In sum, sleeving an engine means more than inserting a tube into a bore. It is a precise reconciliation of wear, material science, and engineering geometry that lets a seasoned block live on as a reliable, tuned component of a machine. It preserves the piston’s working environment, restores the seal necessary for compression, and, when applied with the right materials and methods, enables improved durability and the possibility of targeted bore customization. It is a telling reminder that in engines, as in many intricate systems, the most critical interfaces—the interfaces between metal, lubricant, and coolant—often determine success more than any single component alone. The sleeve, once installed and finished, becomes a new chapter in the engine’s lifecycle, one that honors the original block while embracing the future through careful engineering.

Inside the Cylinder: Dry vs Wet Sleeves and the Quiet Balance of Heat, Seal, and Strength

Every engine hinges on the integrity of its cylinder walls. Over thousands of cycles, heat, pressure, and the simple abrasion of moving parts take a toll on the bore, leaving scoring, loss of cross-sectional area, and a taper that robs compression and efficiency. Sleeving an engine—the deliberate installation of a new inner surface inside the old cylinder bore—emerges as a practiced repair that restores dimensions, improves sealing, and can reclaim performance without the heavier decision to replace a complete block. The technique is most common in diesel power plants, older performance engines, and larger industrial or marine applications where the cylinder must cope with stubborn wear and demanding duty cycles. In its essence, sleeving is a careful act of engineering that redefines the working interface between piston and wall, bringing a fresh surface into contact with the piston rings and the lubricating oil that carries them. Yet the method is not monolithic. It splits into two main families—dry sleeves and wet sleeves—each with distinct construction, cooling pathways, and implications for heat management and seal integrity. The choice between them is not merely a matter of preference but a question of thermal physics, mechanical fit, and the intended duty cycle of the engine.

Dry sleeves sit inside the block but do not carry coolant directly. They are typically pressed into a precisely bored hole and rely on the block itself to conduct heat away from the sleeve area. The sleeve is sealed from the coolant by the surrounding block and the head gasket that seals the interface to the cylinder head. In this arrangement, the sleeve’s structural support derives from the block’s walls and the interference fit created during installation. The sleeve’s exterior is designed to be compatible with the bore and the piston’s diameter, while the interior surface forms the new, uniform ringland for the piston rings to ride against. The material choices here lean toward hard wear-resistant metals, often cast iron or similar alloys, chosen for their ability to resist piston-ring wear and to translate heat into the surrounding block with predictable behavior. Since the sleeve itself is not in direct contact with the coolant, cooling remains a function of the block’s coolant passages and the efficiency of heat transfer through the bore wall into the surrounding coolant stream.

The heat flow path in a dry-sleeved engine is a drumbeat of finite resistance. The sleeve accepts heat from the piston rings and the bore wall; it then transfers that heat into the block, which carries it to the coolant channels. The design boundary here is the interface: the sleeve’s outer diameter must press tightly enough to stay in place under vibration and thermal cycling, yet not so tightly as to induce microcracking or an unacceptable distortion of the bore. The relentless thermal cycling of the engine, especially at high power or in hot climates, compresses the tolerance window. If the bore is oversized or the interference is insufficient, the sleeve can rotate or creep, compromising seal integrity and leading to ring wear or loss of compression. If the interference is excessive, the bore, the sleeve, or both can crack or warp under load, producing an expensive failure that may require re-boring or an even more invasive repair. On the other hand, a well-executed dry-sleeve installation acts as a durable, long-term refurbishment, restoring the cylinder to a consistent, straight, and round geometry that supports reliable ring seal and predictable combustion dynamics. For readers seeking a deeper dive into engine sleeves themselves, consider the detailed explanation available in expert resources, such as the linked explainer: Sleeve an engine explained.

Wet sleeves, by contrast, are designed to live in direct contact with the coolant. These sleeves are sealed at the top and bottom to prevent leakage, forming a separate coolant jacket around the interior bore. The sleeve itself is commonly manufactured from materials that can withstand the dual demands of high-temperature combustion environments and corrosive coolant, frequently stainless steel or specialized alloys that resist rust and chemical attack. The outer surface of a wet sleeve is engineered to be in intimate contact with coolant, drawing heat away efficiently and reducing the thermal gradient across the sleeve wall. The design’s strength lies in cooling effectiveness, which is a critical advantage when engines endure high thermal loads, aggressive operating regimes, or sustained high-speed operation. Because the sleeve is surrounded by coolant, heat removal is more direct, so the engine can tolerate higher peak temperatures and more aggressive timing and fuel strategies without detonation or piston scuffing. However, the direct coolant exposure imposes tighter sealing requirements. The top and bottom of the sleeve are typically fitted with O-rings or specialized seals that prevent leaks into the block or into the combustion chamber. Any imperfection in the seal, a minor mismatch in bore dimensions, or a minor shift in sleeve position can translate into coolant loss, coolant contamination of oil, or, in extreme cases, gasket failure. This is why wet sleeves, while offering superior cooling, demand precise machining, meticulous assembly, and rigorous quality control. The machine work must ensure a uniform bore, a perfectly perpendicular sleeve axis, and a press fit that remains stable under hot-cold cycling.

The practical differences between these two configurations begin to shape the engine’s character in subtle, but consequential, ways. A dry sleeve’s cooling is mediated by the block, which means that the block’s geometry and coolant flow become critical to overall heat management. If the block’s cooling passages are well designed, the surface temperature of the sleeve remains within an optimal range and the piston rings maintain a stable seal. If heat removal is sluggish, the bore can evolve a curvature or a micro-warp under load, potentially increasing oil consumption, reducing ring seating efficiency, and shortening the life of the sleeve and the piston rings. In some engines, the dry sleeve must bear more load because the outer cylinder wall carries a larger share of the heat transfer away from the wall, whereas in other designs the sleeve is comparatively insulated by the block’s design. The dryness of the sleeve also tends to simplify the coolant system; there is no need for the additional sealing interfaces at the top and bottom of the sleeve, and the assembly can be somewhat more forgiving of minor dimensional tolerances in the coolant side. The cost and complexity of blocks that accommodate dry sleeves can be lower, and the downtime for installation can be shorter, especially when the block geometry is already close to the target bore size.

Wet sleeves, with their direct coolant exposure, invite a different calculus. They allow far more aggressive cooling, which translates into the possibility of higher power output before heat becomes the limiting factor. This is why wet sleeves are prevalent in large diesel engines found in ships and stationary power plants where sustained high output is the norm and cooling demand is constant. The robust seals that keep the coolant separate from the combustion environment are crucial; even tiny leaks can escalate into coolant loss, compression loss, oil contamination, or corrosion-driven failures. The complexity of wet sleeves can raise both the initial cost and the maintenance burden. Yet when done right, they offer a durable, reliable cooling path that supports larger operating envelopes and higher resistance to thermal fatigue. This advantage is often decisive in high-load, high-hour life cycles where reliability under heat stress is paramount.

The decision between a dry or a wet sleeve is not simply about what the machinist prefers. It is a design choice that reflects the engine’s duty cycle, the available cooling capacity, and the acceptable risk profile. A block built around a dry sleeve will typically assume that the block provides the primary thermal path and structural support, while a wet-sleeve approach assumes the coolant will directly affect the bore wall. In practice, the machinist’s skill and the engine’s service history guide the choice: a road-going engine that spends long hours in moderate heat may benefit from a dry sleeve’s simplicity and robustness, while a marine or industrial engine operating near its thermal limit may gain more from the exacting cooling afforded by a wet sleeve.

From an installation perspective, sleeving a bore is both an art and a science. For a dry sleeve, the bore must be perfectly cylindrical, with concentricity that aligns the sleeve’s axis with the crank and the piston stroke. The press-fit tolerances are tight, and the sleeve must not shift during heat cycles or under the torque of the head bolts. The bore geometry must be preserved through reaming or honing to ensure the piston rings seal evenly and the compression remains uniform around the circumference. In the wet-sleeve scenario, the machining work extends to the exterior bore’s interface with the coolant passages; the sleeve’s outer surface must mate precisely with the block’s coolant jacket, and the sealing system must be uninterrupted around the full circumference. The seals at the top and bottom must tolerate expansion and contraction due to temperature swings while remaining leak-free. The cost of this precision is not trivial, but the payoff is clear in engines designed for heavy duty, long life, and high thermal loads.

Beyond the installation, the sleeve’s life cycle is defined by how well the engine is maintained and how consistently the cooling system operates. The signs of trouble differ with sleeve type. In a dry-sleeved engine, signs of trouble might include increasing oil consumption due to imperfect ring seal, slight loss of compression, or a bore that has become subtly out-of-round under load. In a wet-sleeved engine, coolant leaks, higher coolant loss, oil-coolant contamination, or unexpected temperature rise can signal a sealing issue at the sleeve ends or a problem with the sleeve’s alignment or seating. Both paths point to the same truth: sleeving is a measure to restore geometry and integrity, but it does not eliminate the need for vigilant coolant management, proper oil quality, and disciplined maintenance practices. The correct coolant chemistry, with buffers and inhibitors suited to the metal and seal materials, becomes as critical as any gasket or ring. If the coolant becomes aggressive, the sleeve’s life is shortened, and the benefits of sleeving can be undermined by corrosion, pitting, or seal degradation.

From a performance perspective, sleeving can unlock a range of benefits. A renewed bore eliminates the scatter of wear patterns that degrade compression and fuel economy. It stabilizes the piston’s travel, reduces blow-by, and can enable more precise ring sealing. In high-performance or rebuilt engines, a properly installed sleeve lets the operator select an oversize piston’s diameter to restore the original displacement or even tailor the bore for a slight increase. This is not a cosmetic fix; it reconstitutes the cylinder’s geometry, which in turn stabilizes combustion, improves heat transfer consistency, and maintains ring seal across a usable operating envelope. Yet the performance gains are bounded by the total engine package: the crank, the cam, the valvetrain, the fuel system, and the cooling loop all share the duty that the bore must handle. Sleeving, powerful as its impact can be, is a component of a broader system, not a standalone magic fix.

In literature and practice, sleeving is often presented as a restoration method that breathes new life into worn blocks without the more drastic step of reworking or replacing the entire engine. Its value grows as engines become larger, older, or more specialized, where the cost and availability of a brand-new block are prohibitive and the owner demands reliability under heavy use. For those evaluating whether sleeving is appropriate, it is worth reading about the differences between sleeve types and their cooling interactions, and then weighing the engine’s operating profile, maintenance capacity, and long-term goals. If you are curious about the broader fundamentals of engine sleeves and their role in restoration and performance, you can explore further with a dedicated explainer on engine sleeves: Sleeve an engine explained. This resource offers a concise, practical overview that complements the technical nuance discussed here.

As with any serious modification, the path to sleeving should be guided by a careful assessment of the engine’s history, the available workmanship, and the anticipated operating conditions. Dry sleeves appeal to those prioritizing simplicity, robust block compatibility, and a milder maintenance footprint. Wet sleeves attract those who demand maximal cooling efficiency, resistance to higher thermal loads, and a design that can tolerate more aggressive duty cycles. The tradeoffs are real and measurable. The machinist must balance bore geometry, sleeve material, and the block’s coolant architecture. The engine designer should consider how the chosen sleeve type interacts with piston rings, lubrication regimes, and heat rejection pathways. Finally, the owner should consider the long-term implications: maintenance intervals, coolant management, and the risk profile of each path. In that sense, sleeving is less a single fix than a calibrated compromise, chosen with eyes wide open toward how the engine will live in real-world service.

For those who want a compact reference to the global rationale behind engine sleeves and the practicalities of their installation and life in the field, the engineering literature and trade publications offer a detailed body of knowledge. The decision to sleeve, and the choice between a dry or a wet approach, is a decision about how the engine will breathe under pressure: how quickly heat is removed, how reliably the rings seal, and how predictable the life of the bore will be under months and years of service. In the end, sleeving a cylinder is not merely a fix; it is a commitment to a carefully engineered interior environment where heat, pressure, lubrication, and geometry align to preserve power, efficiency, and durability. For readers seeking a broader view of sleeving concepts and cost considerations, there is a dedicated overview that provides context for the engineering calculus behind sleeves and their lifecycle costs: https://www.enginebuildermag.com/technical-articles/engine-sleeving-explained.

Sleeving an Engine: Balancing Cost, Craft, and Longevity in Cylinder Restoration

Sleeving an engine is more than a repair maneuver; it is a strategic choice about the life story of a machine. When the walls of a cylinder wear or suffer damage, the piston’s path becomes a struggle between precision and wear. A sleeve, a replaceable cylindrical liner, becomes the new inner surface the piston and rings meet every revolution. In larger engines and particularly in diesel and high-load applications, sleeving preserves block integrity and restores compression without the monumental cost and downtime of a full block replacement. The technique sits at the intersection of engineering discipline and economic pragmatism. It is a choice that has to be justified not just in terms of whether it can be done, but whether it should be done given the clock, the budget, and the performance expectations placed on the engine in question. The plain question—what does sleeving an engine mean?—thus unfolds into a broader examination of why sleeves exist, how they work in practice, what trade-offs they entail, and how market realities shape the decision to sleeve rather than to replace, bore out, or rebuild around a different core.

At the most fundamental level, sleeving restores cylinder bore geometry. The worn bore sets a limit on piston rings, clearance, and the engine’s ability to seal effectively. Worn bores lead to increased blow-by, higher oil consumption, reduced compression, and poorer combustion efficiency. In a modern sense, sleeving gives engineers and technicians a controlled starting point. A sleeve creates a uniform, round, and well-lubricated surface, which is especially important when the original block has suffered localized wear, corrosion, or damage that would complicate a repair with conventional machining alone. The sleeve serves as a fresh canvas for the piston rings, with a bore diameter and surface finish that can be tailored to the engine’s operating regime. This is particularly valuable in diesel engines and heavy-duty applications where the margin for error in bore integrity is small and the environmental and economic costs of failure are high.

Two broad sleeve philosophies guide most practical decisions: dry sleeves and wet sleeves. Dry sleeves are pressed into the block and do not touch the cooling system, or they are sealed from coolant contact elsewhere in the bore. Wet sleeves, by contrast, sit in direct contact with the engine’s cooling circuit and are sealed at the top and bottom to prevent coolant leakage into the combustion chamber. Each type offers its own advantages and challenges. Wet sleeves interact more intimately with heat transfer, a factor that matters in high-load, high-temperature cycles where thermal conductivity can influence engine life and efficiency. Dry sleeves simplify coolant dynamics and can reduce the risk of leak pathways around the sleeve wall, but they demand tighter control of interference fits and block deformation. The choice between dry and wet sleeves is not merely a matter of engineering preference; it is a decision shaped by the engine architecture, the expected service conditions, and, crucially, the economics of repair versus replacement.

From an economic standpoint, sleeving shines where the alternative is replacing a block or the entire engine. A new block can consume a large fraction of a major overhaul’s cost, especially in older or specialized engines where parts supply and machining take up a significant share of the budget. Sleeving, when carefully executed, offers a cost-effective path to restoring power and reliability without discarding a familiar core. Modern sleeves are built from advanced materials—high-strength cast iron and steel alloys with coatings designed for wear resistance and heat tolerance. This matters, because the sleeve’s material dictates how well it resists pitting, micro-wear, and the thermal cycling that accompanies heavy use. It also influences the piston ring seal, oil control, and the potential for gas blow-by to degrade over time. In fleet operations, where uptime is a currency, sleeves can translate into shorter outages and longer intervals between major overhauls, thereby lowering total lifecycle costs.

The economic calculus is layered. It begins with the obvious line item: the sleeve kit, the machining, and the labor for installation. But it extends into downstream costs that are easy to overlook. A properly sleeved engine can deliver consistent compression ratios and sealing characteristics, which in turn affect fuel efficiency and emissions. The bore surface finish and the chosen coating regime can alter piston ring seating behavior, oil film stability, and heat transfer. The more exactly the sleeve harmonizes with the piston, rings, and lubrication system, the more predictable the engine’s behavior in daily operation. This predictability—less blow-by, steadier oil consumption, tighter tolerances—contributes to a lower total cost of ownership over the engine’s life. Conversely, a sleeve that is installed with misalignment or improper bore sizing raises the risk of accelerated wear, leakage, or premature failure, eroding any initial savings and potentially triggering repeated interventions.

To translate these technical implications into decision-ready criteria, operators must consider the engine’s application profile. In stationary or marine settings, where an engine runs for extended periods at relatively stable loads, the benefits of sleeves in terms of durability and heat management are pronounced. In heavy-duty on-road fleets, the demand for reliability and predictable maintenance windows makes sleeves attractive if the block has sufficient remaining life and the installation teams possess the requisite precision. In agricultural or industrial settings that see heavy cyclical loads or harsh operating environments, sleeves can protect the core block from localized fatigue and failure modes that would otherwise shorten service life. In all cases, the decision rests on a blend of measured technical feasibility and disciplined economic analysis: what will the total cost over the next few years look like with a sleeved block, versus a bore and rebuild, or versus a block replacement?

The practical path to sleeving involves a sequence of precise steps, each with its own cost and risk profile. Machining the block to the required tolerances is not trivial. The bore must be prepared with an even roundness and a consistent finish that influences friction, wear, and oil retention. Interference fit, press-in or slip-fit processes, and the heat-treatment history of the block all influence sleeve life. A misstep at this stage can produce axial or radial misalignment that translates into uneven ring wear, poor sealing, or early sleeve leakage. Even with the correct fit, the surface finish of the sleeve must be tailored to the engine’s operating envelope. The sleeve may require a particular bore finish or a coating to control wear rates and heat transfer. These preparation choices are not cosmetic; they define how the engine will behave under high load, high temperature, and sustained operation.

Installing a sleeve also demands careful alignment with the engine’s lubrication and cooling systems. The seal between the sleeve and the cylinder head or deck surface is critical to preventing coolant leakage into the combustion chamber and to keeping oil from migrating into the bore. The compatibility of the bore with piston ring geometry—ring tension, tension distribution along the bore, and ring seal performance—depends on the clean, consistent bore diameter that sleeving enables. The longer the sleeve life and the better the seal integrity, the more stable the engine’s performance, with reductions in oil consumption and emissions spikes that otherwise accompany worn bores. These technical realities intersect with economic considerations: every fraction of a millimeter of wear avoidance, every kilometer of reliable sealing, and every hour saved in downtime accumulate into meaningful lifecycle benefits when the engine is part of a larger fleet or a critical industrial process.

An important practical nuance is the balance between precision and pragmatism in installation. Sleeving walls off some of the uncertainty inherent in worn blocks by offering a fresh, engineered surface. Yet the benefit only accrues if the installation is performed by skilled technicians using appropriate equipment. The cost of labor and the risk of warping or distortion during sleeving are real. That is why even when sleeves promise a favorable payback, the upfront investment in skilled machining, alignment checks, and quality assurance can be significant. In some cases, this is mitigated by the block’s existing condition and the degree of remaining material before wear becomes a structural concern. In others, it is mitigated by the availability of a sleeve kit designed for a particular bore diameter, the choice of dry versus wet sleeve, and the engineer’s confidence in heat management and longevity under the engine’s duty cycle.

Beyond the immediate mechanics, sleeving invites a broader discussion about how modernization and retrofitting interact with traditional cylinder design. Sleeve design can influence not only wear resistance but also how the engine responds to different fuels or lubricants. Some sleeves are built with surfaces that optimize combustion chamber dynamics and reduce oil blow-by, while others focus on durability under high-load, high-temperature conditions. In this sense, sleeving is not simply replacing a worn surface; it can be a platform for targeted performance improvements aligned with a given operating regimen. The ability to tailor sleeve materials and finishes to a specific application—high-load or high-temperature environments, or engines tuned for efficiency rather than raw power—adds a layer of flexibility that enhances the economic case. It allows operators to preserve a core asset while steering performance in a direction that aligns with evolving requirements, whether that means reduced maintenance costs, longer intervals between overhauls, or improved fuel economy.

To connect the technical with the economic, consider how sleeve material science threads through the decision process. The sleeve’s base material—often cast iron or steel alloys—anchors wear resistance and heat tolerance. Advanced coatings further extend service life and dampen wear mechanisms that would otherwise degrade the bore after countless cycles of combustion, expansion, and contraction. This material sophistication translates into fewer interruptions for ring seating, less degradation of the compression profile, and a more predictable oil control regime. Each of these outcomes reduces the risk of unexpected downtime and curtails the financial shock of emergency repairs. The practical implication for fleet managers is that sleeving can transform a potentially life-limiting wear pattern into a managed risk with a defined maintenance cadence. That cadence, in turn, feeds directly into budgeting, downtime planning, and overall asset reliability.

In the end, the decision to sleeve is a calculation with many moving parts. It requires a clear-eyed appraisal of the engine’s current state, the expected service life post-repair, and the total cost of ownership across the next several years. The economics are not simply about initial cost savings. They hinge on the sleeve’s ability to restore integrity, maintain efficiency, and hold up under the particular stresses of the engine’s operational profile. This is where the practical craft of sleeving meets the strategic calculus of maintenance planning. When done well, sleeving can yield a durable, reliable, and economical path back to peak or near-peak performance, preserving the core asset and delivering value that outlives the initial repair bill. When done poorly, it can become a costly stopgap that masks deeper structural issues or leads to premature rework.

For readers seeking a deeper technical dive into the materials and processes behind modern cylinder sleeves, further reading on sleeve materials and their innovations can illuminate how a sleeve’s composition supports its role in performance and longevity. This broader context helps explain why sleeving remains a favored option in the right circumstances and why it is not a universal solution for every worn bore. The central takeaway remains practical and clear: sleeving redefines what is possible with an aging block, turning wear into a controlled, measurable variable rather than an unpredictable fate. It is a choice that rewards careful engineering, disciplined execution, and a holistic view of lifecycle cost. When the economics align with the technical feasibility, sleeving becomes a prudent path to restore, rather than replace, the engine’s core power train.

For a concise financial perspective that translates the engineering into a cost framework, see the dedicated discussion on engine sleeve cost. This resource outlines typical cost components and how they map to expected service life and downtime planning, helping operators compare sleeving with block replacement or rebuild options. engine sleeve cost

External reference:

For a thorough technical explanation of sleeving and its practical implications, an external resource offers a comprehensive overview of the concepts, materials, and processes involved in engine sleeving. https://www.enginebuildermag.com/technical-articles/engine-sleeving-explained

Final thoughts

Sleeving an engine is a targeted repair option that preserves block integrity while renewing the inner surface the piston relies on. By understanding the purpose and mechanism, readers can evaluate when a sleeved bore is preferable to a full block rebuild. The dry-versus-wet sleeve comparison clarifies heat management and coolant interaction—critical factors for longevity in motorcycles and autos, where compact cooling designs and high heat loads test durability. Finally, weighing economic and practical considerations helps shops and owners forecast downtime, tooling needs, and long-term reliability. Used thoughtfully, sleeving can extend engine life, protect resale value, and maintain performance without the overhead of a complete engine replacement.