Engine enthusiasts, motorcycle owners, auto owners, parts distributors, and repair professionals alike often run into a layered web of part numbers when dealing with Cummins engines. The 4T390 is frequently mentioned in catalogs and on supplier pages, but it is not an engine model. Instead, it is a gasket kit part number associated with Cummins engines such as the 4BT3.9 and related B-series units like the 6BT. This distinction matters: you can neither sleeve nor bore a gasket kit, but you can sleeve a cylinder using a liner in a rebuild. On the other side of the ledger, the cylinder liner part number 3904166 is commonly used in the 4BT3.9, and it is offered in standard and oversized sizes—clear evidence that the 4BT3.9 engine is sleeved, with replaceable liners that restore critical bore geometry during maintenance and overhauls. For shop owners, technicians, and distributors, the practical implications are straightforward: misinterpreting 4T390 as an engine can lead to ordering errors, while recognizing that sleeving is a standard repair path helps plan materials, tooling, and timelines more accurately. The chapters that follow build a complete picture—from defining what 4T390 actually refers to, to the sleeving process, to the distinct roles of gasket kits versus sleeves, to the real-world impact on rebuilds and maintenance, and finally to sourcing and official guidance from Cummins. By the end, you’ll have a practical framework to discuss sleeving options with customers, verify part compatibility, and coordinate with authorized distributors and repair facilities.

Sleeves, Part Numbers, and the Real Engine Behind 4T390 Confusion: Clarifying Sleeving in the 4BT3.9 Family

A stray code in conversation or a mislabeled parts list can send a reader down a winding path of assumptions. When people encounter the term 4T390 in relation to Cummins engines, the tendency is to think they’re discussing a specific engine model or a ready-made sleeve kit for a given block. In truth, 4T390 is commonly a gasket kit part number, not an engine model. The misinterpretation is understandable because students and technicians alike are trained to read the digits and letters as if they describe a single, self-contained unit. The longer, more accurate map, however, sits in the distinction between a gasket kit designation and the actual engine family that uses cylinder liners. The engine family most associated with this kind of sleeving is the 4BT3.9, a durable four-cylinder diesel that sits in the lineage of Cummins’ B-series designs. Understanding this subtlety matters, because sleeving is not a vague concept or a marketing term. It is a precise engineering solution, and in the context of the 4BT3.9, it reveals how the block is designed to be rebuilt, machined, and restored to life through replaceable cylinder liners.

From a practical standpoint, the key to the confusion lies in the language: a gasket kit part number like 4T390 is tied to gaskets, seals, and associated consumables used during a rebuild. It is not the engine block, not the model, nor the sleeve itself. By contrast, the 4BT3.9 engine is a concrete architectural family within Cummins’ larger catalog. It is a four-cylinder, inline, turbocharged diesel that uses cylinder liners inside the engine block—a sleeve system, in other words. The liners are not only a design feature but a functional requirement. They provide replaceable contact surfaces for pistons, control wear, and allow the engine to be rebuilt with new walls rather than a new block when wear or damage accumulates. In this sense, the 4BT3.9 is sleeved; the sleeves are replaceable liners that live inside the block and are cooled by the engine’s coolant system.

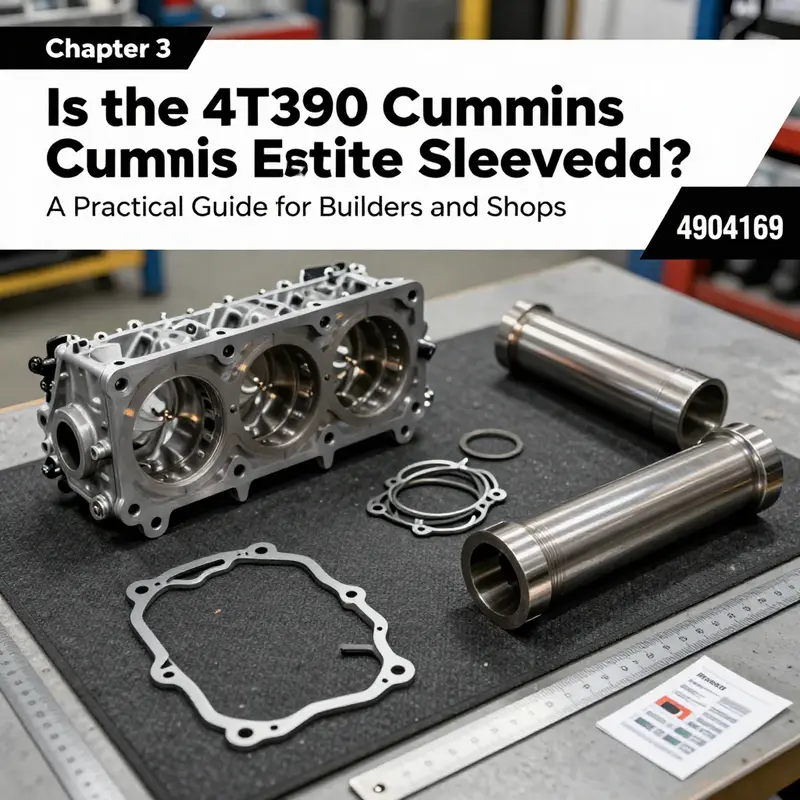

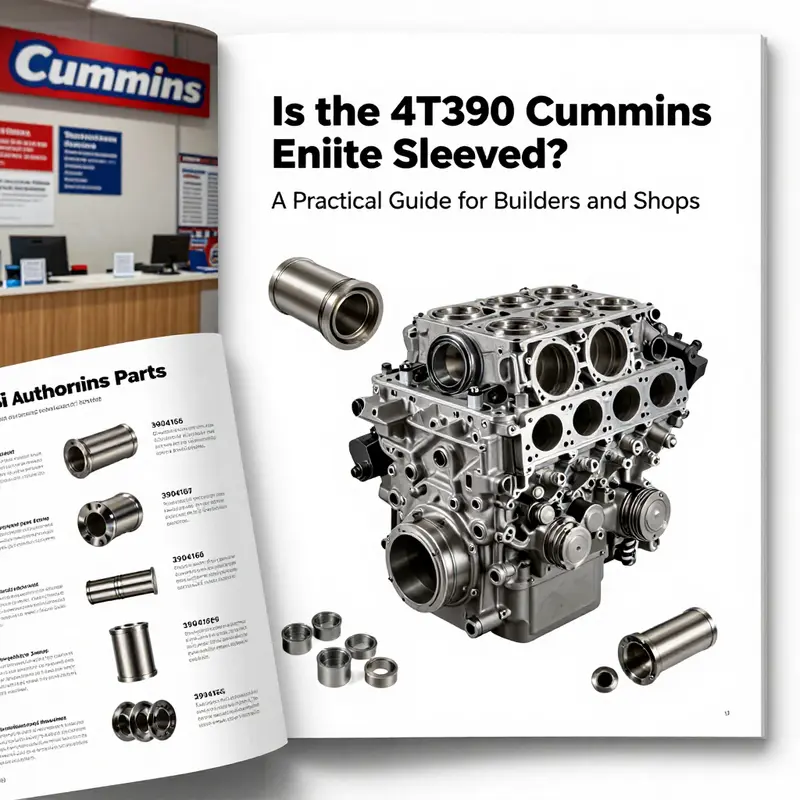

A concrete point often cited by practitioners is the part number 3904166, a cylinder liner associated with the 4BT3.9 and other engines in the same B-series family. This part number is an explicit reminder that sleeves aren’t just a conceptual feature; they are manufactured components available in standard and oversize sizes. The oversize options are crucial for professional rebuilds when wear has advanced beyond simple honing. The existence of standard and oversized liners signals a broader design intention: the block can be restored to exacting tolerances through controlled material removal and precise reassembly. The chain of care does not end with pulling old sleeves and pressing in new ones. It continues with careful measurement, selecting the proper oversize to achieve correct bore diameter, and ensuring the liner height and seating surface align with the block’s deck surface, head gasket surface, and cooling passages.

To a technician, the distinction between a sleeved engine and a block that has undergone a simple bore and hone is significant. Sleeving implies a live, replaceable surface that can be refreshed without replacing the entire block. It suggests a process that begins with a thorough inspection: checks of the block’s main bores, deck height, and cylinder head surface, followed by a precise bore operation to restore a clean, true plane for liner seating. When liners are installed, they must be sealed and cooled; gaskets, o-rings, and coolant passages must fit in exact alignment. In this context, the 3904166 liner isn’t just a piece of hardware; it is a calibrated interface between the engine’s core and its wear path. The ability to source standard and oversized liners means a rebuild can be tailored to the engine’s actual wear state, rather than a one-size-fits-all repair.

The practical implications of sleeving for the 4BT3.9 extend into maintenance philosophy, parts management, and long-term performance. A sleeved engine carries the advantages of updated bore geometry and restored compression chamber conditions. The liners themselves can be manufactured to tight tolerances with finishes suitable for the piston rings and lubrication regime in a four-stroke diesel. However, the process demands precision and discipline. Block cleanliness, liner seating, and the sealing interface with the coolant system are critical. A poorly seated liner can lead to coolant leaks, loss of compression, or abnormal wear, quickly undermining the gains of a rebuild. These considerations underscore why a misnamed part number such as 4T390 can mislead a technician into ordering the wrong kit and missing the crucial element—the actual sleeving kit that addresses cylinder walls.

In telling this story, it becomes clear that the term sleeved is not about a single bolt-on piece; it is a design principle embedded in the block, expressed through replaceable liners and a tailored set of maintenance steps. For the 4BT3.9 and its siblings, the sleeves permit a lifecycle that supports heavy-duty use—from agricultural machinery to industrial equipment—without requiring a brand-new block when wear becomes excessive. This concept aligns with the broader discussion of cylinder sleeves, which exist in both wet and dry configurations, and which can be chosen based on the engine’s cooling strategy and the operator’s performance requirements. A wet-sleeve approach, common in many heavy-duty designs, places liners directly in coolant contact, which demands careful attention to seal geometry and coolant quality. Dry sleeves, by contrast, sit inside the bore without in-block coolant contact, offering different thermal management characteristics. The 4BT3.9 belongs to a family where the liner system is central to rebuild strategy, and where oversize liners open pathways to restoring compression, avoiding the need for oversized pistons and crankwork changes beyond the necessary scope.

For readers who want a quick primer on how engine sleeves work in a general sense, a concise explainer can provide a bridge to the specifics of the 4BT3.9. Engine sleeves explained offers a grounded overview of why sleeves exist, how they are installed, and what to expect during a typical rebuild. This background helps anchor the more precise discussion of a gasket-kit designation like 4T390 and its real-world implications for sleeving within the 4BT3.9 lineage. The goal is not to get lost in nomenclature, but to connect the dots between identification numbers, the mechanical reality of liners, and the practical steps engineers and technicians take when restoring life to an aging but reliable diesel block.

As the narrative continues toward the broader arc of engine restoration, the technical distinctions matter less as abstract terms and more as a map for the shop floor. The sleeve, in this sense, becomes a tangible boundary object—something you measure, order, and install with a precise method, and something that ultimately defines the engine’s potential longevity. Knowing that 4T390 is not a model, but a gasket kit designation, helps prevent costly misorders and misapplications. It also clarifies why the 4BT3.9’s sleeved design is a centerpiece of its rebuild philosophy. In the hands of a skilled technician, the liner approach can deliver a renewed cylinder bore with predictable wear characteristics, restored compression, and a reliable base for continued operation under demanding conditions. The chapter thus returns to its core aim: to disentangle a common misreading and to illuminate the mechanical reality that lies beneath the numbers.

For those seeking official specifications and a formal frame of reference, consult the engine’s official documentation. Official specifications and details can be found here: https://www.cummins.com/en/products/engine/4bt3.9

Sleeving the 4BT3.9 Cummins: Cylinder Liners, Sleeves, and the Rebuild Path from Gasket Kits to a Durable Block

There is a common confusion surrounding the label 4T390 in Cummins parlance. It isn’t a model name for an engine; it’s a gasket kit part number associated with Cummins diesel platforms, notably the 4BT3.9 family and related B-series engines. That distinction matters because it shifts the starting point of any sleeving discussion away from a simple kit and toward the heart of the engine block: the cylinder liners. The 4BT3.9 is designed to use replaceable cylinder liners, a feature that keeps the engine viable through multiple rebuilds without sacrificing the integrity of the block itself. In catalogs and repair guides you’ll often see the liner part number 3904166 cited as a standard replacement, with oversize options available to restore bore diameter and maintain compression after wear or bore distortion. This arrangement means that a rebuild can proceed in a controlled sequence: measure and assess wear, choose the correct liner size, install the sleeves, and then perform any needed finishing machining to bring everything into spec. The outcome is a durable, reliable core that can withstand the high pressures and temperatures characteristic of diesel operation, while offering a practical path to long-term maintenance instead of premature block replacement.

To appreciate why sleeving matters, it helps to step back from the kit label and consider the role of the liner itself. The liner functions as the inner surface of the cylinder bore, providing a hard, wear-resistant surface for piston movement and ring sealing. Its geometry, surface finish, and alignment with the crankcase, deck, and head gasket layers all contribute to how the engine holds compression and how efficiently it converts fuel into power. In a four-stroke diesel, where heat is intense and thermal cycling is relentless, the liner’s resilience is the engine’s quiet backbone. When a bore wears or scars, the entire compression profile can be compromised, and the engine’s efficiency and emissions can suffer. Replacing worn liners with correctly sized sleeves is a practical, repair-friendly approach that preserves the block’s core integrity while renewing the engine’s breathing surface.

The sleeving process itself is a careful, multi-step operation that blends metrology with precise machining. Technical guides describe a sequence beginning with accurate mandrel measurements to establish the acceptable runout and concentricity. Manufacturers emphasize careful grinding of the bore to prepare a true, even seating surface for the new sleeve. After final measurements confirm tolerance bands, the sleeves are pressed or fitted into position, and the assembly is checked for alignment and surface finish. The goal is not merely to drop in a new part; it is to ensure a perfectly aligned, sealed cylinder pairing where the liner’s outer surface mates seamlessly with the block’s counterbore, head gasket seat, and cooling passages. A properly sleeved cylinder must accept the piston rings without galling, maintain a stable bore diameter under load, and avoid any step or misalignment that would rob compression or promote oil past the rings. The finishing work, which may include light honing or minor contouring, is designed to achieve the clean, round bore required for consistent combustion and durability. In practice, this means that the sleeving process is as much about precision control as it is about replacing a worn part.

For those who work with or study these engines, the practical implications are meaningful. Sleeving a 4BT3.9 block can extend the life of a machine that otherwise might require a costly block replacement or a complete engine overhaul. It also offers a path to calibration and reliability, since liners can be selected to restore original clearance and tolerances. The choice between standard and oversize liners enables technicians to correct bore wear and restore compression while preserving the engine’s fuel timing, injector alignment, and overall geometry. Importantly, the process emphasizes compatibility between the liner and the block, including proper sealing at the top and bottom surfaces, and a secure seal against coolant and combustion gases. This compatibility is central to achieving a dependable rebuild, especially in heavy-duty use where diesel engines bear the brunt of workload and temperature fluctuations.

The broader topic around the 4T390 label—namely how gasket kits interface with sleeves—highlights an essential point for shop practice and planning. A gasket kit referenced as 4T390 sits alongside the liner kit in the broader rebuild workflow, serving as the finishing piece that reassembles the engine’s sealing surfaces once the liners are correctly installed and confirmed. The efficiency of a rebuild hinges on this interplay: the liners offer a refreshed internal wear surface, while the gasket kit ensures a proper seal around the block, head, and associated passages. In many repair scenarios, the ability to sleeve the block first and then complete the reassembly with a fresh set of gaskets and seals translates into a smoother restoration process and a longer-lasting result. From a logistical standpoint, this approach also helps with maintenance planning, as fleets can budget for renewals in stages, aligning spare parts availability with service intervals and downtime windows.

For readers seeking a succinct primer on the concept behind engine sleeves, a helpful overview is available here: What are engine sleeves?.

The practical takeaway is clear. The 4BT3.9’s sleeved design is not an anomaly but a deliberate, durable engineering choice. It makes the engine repairable and serviceable, aligning with the realities of heavy-duty diesel operation where downtime matters and block replacement is costly. Sleeving is a controlled restoration of the bore’s geometry and wear surface, not a simple patch. When done properly, it returns a block to near-original tolerances, preserves compression, and keeps the engine performing reliably in demanding applications. For operators, workshop managers, and technicians, understanding this pathway helps in planning a rebuild, choosing the right replacement liners, and communicating scope and cost with stakeholders. It also clarifies why terms like “gasket kit 4T390” and “cylinder liner 3904166” appear in the same repair discussions—because both components anchor the same rebuild objective: a durable, rebuildable heart for the 4BT3.9 that can endure the rigors of diesel life.

For those who want to delve deeper into the technicalities of sleeving and its material realities, a comprehensive technical guide on cylinder sleeving is available for reference: Cylinder Sleeving | PDF | Engines. This resource provides a broader engineering perspective on machining tolerances, liner materials, and fitment considerations that apply across many diesel platforms and help explain why precise measurement and finishing steps matter so much in practice. https://www.engineersedge.com/manufacturing/cylinder-sleeving.pdf

Chapter 3: Decoding Gasket Kits and Cylinder Liners in a Sleeved Four-Cylinder Diesel Engine

A rebuilt engine is only as reliable as the parts that keep it sealed and the bore that houses the moving parts. In discussions about the four-cylinder diesel family that underpins many industrial and light-duty applications, two concepts often get crossed: gasket kits and cylinder liners. They belong to different realms of a rebuild. Gasket kits are all about sealing the interface between stationary sections and moving components—keeping oil, coolant, and combustion where they belong. Cylinder liners, by contrast, are the metal sleeves that line the bore, forming the wear surface for the piston and rings. Confusion is common because both play crucial roles in a rebuild, and both can be involved in the same overhaul. Yet the maintenance implications of each are distinct. Understanding the separation between these two elements helps ensure a durable repair, better longevity, and fewer leaks or bore defects after the rebuild.

A typical overhaul begins with identifying what must be replaced through inspection and measurement. The gasket kit is the catalog of seals and gaskets that will be swapped to restore the engine’s seals. In a four-cylinder diesel engine, a comprehensive overhaul kit generally covers the major sealing surfaces: the head gasket that seals the combustion chamber to the cylinder head, the valve cover gasket, intake and exhaust manifold gaskets, the oil pan gasket, and the front cover gasket. There will also be a gasket to seal between the turbocharger and its plumbing, along with camshaft seals, oil filter adapter gaskets, and the assortment of O-rings and small seals that are prone to hardening with heat and age. The exact contents can vary with the engine’s configuration and the builder’s preferences, and the specific kit you order will hinge on the serial number, build date, and the internal components installed in that unit. This means that compatibility is not a matter of generic fit alone; it must be cross-checked against the engine’s configuration and the intended service plan.

Because gasket materials and seal profiles evolve, a key practice in planning a rebuild is to verify compatibility against the engine’s family and build history. If the engine currently uses a particular head gasket thickness, or if certain sealing surfaces have been machined or modified, the corresponding gaskets must reflect those changes. In practice, this means that the gasket kit chosen for a rebuild is not merely about the number of seals it contains; it is about the flow paths, the bore and deck clearances, and the torque sequences that govern how these gaskets behave under heat and load. Incorrect gasket selection can translate into leaks, loss of compression, or coolant migration, undermining the rebuild before it even runs enough to break in. The simple takeaway is that gasket kit cross-referencing must be precise, anchored in the engine’s serial information and the rebuild scope.

If you peel back another layer of the overhaul, you encounter the cylinder liner—the engine’s wear surface. Cylinder liners, or sleeves, are replaceable metal sleeves that line the bore and serve as the true wall against which the piston rings ride. In many engines of this family, the cylinder bore can be restored through sleeving, which allows a worn bore to be rebuilt to standard or oversize specifications. The liner approach offers a controlled bore diameter, a fresh surface, and improved resistance to scoring and seizure. In practical terms, sleeving is the main strategy when the bore has excessive wear, corrosion, or ovality that cannot be corrected by honing alone. In a sleeved arrangement, the engine block receives one or more replaceable liners that sit in machined recesses, each liner then providing a new, concentric bore for the piston and rings. Depending on the engine design, these sleeves can be dry or wet, and they can be installed in standard or oversize forms to restore the correct piston clearance and ring land geometry.

The sleeve conversation is not just about size; it is about how the sleeves interface with other systems. Wet sleeves, which are immersed in coolant, demand careful management of the coolant passages, the sleeve seating depth, and the sealing at the head and bottom lands. Dry sleeves, which are not bathed in coolant, place different demands on the block’s cooling strategies and the fit between the liner and the block. The choice between wet and dry sleeves has practical implications for machining tolerances, coolant flow, and the long-term heat management of the engine. In the four-cylinder family, the sleeve choice is dictated by the original design and subsequent rebuild decisions. When you see widely available sleeve replacements in standard and oversize forms, it signals that sleeving is commonly used to salvage or enhance the engine’s bore after wear or damage. Sleeving, in effect, is the core method for reclaiming a bore without replacing the entire block, a more invasive and expensive proposition.

From a technical planning standpoint, sleeve and gasket considerations often converge during a major service. When you plan a rebuild, you will evaluate whether the existing bore can be restored by honing and reusing the original sleeve, or whether a full sleeve replacement is necessary. The decision hinges on measurements: bore diameter, taper, out-of-roundness, and the integrity of the block, including any porosity or core flaws. If sleeving is pursued, you’ll specify the liner size based on the target piston clearance and the engine’s bore tolerance. Oversize liners may be used to reclaim an oversized bore and snug up clearances that have widened due to wear. The selection process then interacts with the gasket kit choice: if a liner change alters the deck height or the seating geometry for the head gasket and intake/exhaust gaskets, you must ensure that the gasket kit remains compatible with the new configuration. In other words, the overhaul is a careful choreography where the bore, the deck, and the sealing surfaces must all align to deliver a clean seal and precise combustion chamber geometry.

The practical upshot is that the gasket kit and the cylinder liners are not interchangeable terms in a rebuild. Each serves a distinct function, yet their successful integration is essential for engine reliability. If the gasket kit is chosen without regard to the bore condition and liner plan, the result can be leaks and compression loss despite a fresh seal. If the liner strategy is pursued without coordinating with the head, intake, and exhaust sealing strategies, cooling and lubrication paths may become mismatched, quietly undermining the rebuild’s durability. This interdependence explains why meticulous part identification matters. Builders must verify the engine’s build date and serial number when ordering a gasket kit and confirm the liner type and size when planning a sleeving job. It is a reminder that modern engines, even within a single family, can be configured in ways that demand precise parts alignment for the long-term health of the machine.

For readers seeking a concise, visual explanation of what engine sleeves are and how they function, see What are engine sleeves?. This resource can help demystify the interface between the liner and the block, and it emphasizes the practical realities of sleeving, which are often the hinge between a successful rebuild and a recurring leak or bore issue. On the topic of sleeves, it is also worth noting that the literature and catalog references often differentiate between standard and oversized liners, a distinction that becomes critical when addressing wear beyond the original factory specification. When planning a rebuild, a careful decision tree for whether to sleeve—and which size to choose—sits at the heart of the project. The goal is to restore proper piston-to-bore clearance, preserve deck integrity, and maintain reliable sealing across all major interfaces.

In closing, the distinction between gasket kits and cylinder liners may seem technical, but it is foundational to a durable rebuild. The gasket kit is the pack of seals that closes the engines’ vital joints and passages, while the sleeves or liners are the durable wear surfaces that define the bore. Both require precise identification and compatibility checks, but their roles are different. The engine’s expected service life rests on the efficiency of their interaction: seals that stay sealed under heat and pressure, and a bore surface that wears evenly with the piston rings. By treating gasket selection and sleeving as complementary but distinct steps, a rebuild becomes a cohesive process rather than a sequence of isolated replacements. The result is an engine that not only starts reliably but also maintains compression, keeps leaks at bay, and operates with predictable thermal and lubrication behavior across its life. External resources can further illuminate the specifics of liner sizing and compatibility in particular configurations, but the guiding principle remains clear: identify the engine’s bore condition first, then align the gaskets and seals to match the restored geometry. External reference: https://www.supplier.com/product/cummins-cylinder-liner-3904166-4bt-6bt-engine-replacement

null

null

null

null

Final thoughts

In the context of the Cummins 4BT3.9 engine, the takeaway is clear: the 4T390 is a gasket kit part number used across Cummins applications, not an engine model and not something that can be sleeved. Sleeving in the 4BT3.9 is accomplished with cylinder liners, notably part 3904166, available in standard and oversized sizes to restore cylinder bore integrity during rebuilds. Understanding these distinctions helps motorcycle and auto owners, repair shops, and distributors avoid part-mismatch pitfalls and plan rebuilds with confidence. When you’re documenting a sleeves-based rebuild, separate the gasket kit needs from the liner or sleeve requirements, verify part numbers against Cummins’ official catalogs or authorized distributors, and maintain a clear trail of parts for warranty and service history. For shops, the practical workflow is straightforward: confirm the need for sleeves, source 3904166 liners as appropriate, reference the 4T390 gasket kit separately for sealing assemblies, and follow Cummins’ official guidance on installation torque, bore clearance, and seating procedures. This approach minimizes downtime, optimizes pricing, and ensures long-term reliability of sleeved engines.