Engine cylinder sleeves are crucial components in the heart of both motorcycles and automobiles, affecting everything from engine longevity to performance. Understanding the materials that make up these sleeves can help motorcycle owners, auto enthusiasts, and repair professionals make informed decisions on maintenance and upgrades. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the common choices like cast iron, examine lightweight alternatives such as aluminum alloys, consider the use of steel in high-performance applications, and delve into advanced materials including ceramic and copper alloys. Each chapter provides essential insights into how these materials influence engine performance, reliability, and overall vehicle efficiency.

Enduring Cast and New Frontiers: How Cast Iron and Its Contenders Shape Cylinder Sleeve Performance

Cylinder sleeves, or cylinder liners, sit at the heart of an engine’s combustion chamber, shaping how pistons interact with the bore, how heat moves away, and how wear progresses over thousands of cycles. They may seem like small, humble components, but the material that forms a sleeve sets the stage for reliability, efficiency, and service life. The choice of sleeve material is a conversation among several demanding requirements: high wear resistance to withstand millions of up-and-down strokes, thermal stability to manage intense heat without distorting, corrosion resistance to endure cooling water and lubricants, and machinability to allow precise fits within the engine block. The modern answer to this balancing act has historically leaned toward cast iron, with boron-modified variants extending the envelope of performance. At the same time, advances in aluminum alloys, specialized steels, and even ceramic and copper-based composites are expanding the toolbox for designers. Reading through the literature and the practical engineering discourse reveals a straightforward truth: there is no single “best” material for all engines. Instead, there is a family of materials, each with a distinct blend of properties that aligns with the engine’s intended duty cycle, fuel type, cooling strategy, and maintenance philosophy. For a concise reference on what these sleeves are and how they function, see the explainer on engine sleeves. What are engine sleeves?

Cast iron remains the backbone of many sleeves, especially in diesel and rugged gasoline applications where durability and heat handling are paramount. Gray cast iron, the traditional workhorse, offers a compelling mix of wear resistance, heat dissipation, and damping. Its graphite network within the iron matrix provides an excellent combination of softness on the surface to resist seizure and enough strength to resist scoring under realistic load and lubrication conditions. The damping characteristic is particularly valuable in engines that experience high vibration levels or irregular combustion events, as it helps manage noise and contributes to smoother operation. Because gray cast iron is relatively easy to cast and machine, it remains cost-effective for mass production. In wet-sleeve and dry-sleeve configurations alike, gray iron provides a reliable, predictable performance baseline that many engine families rely on when service life, maintainability, and total cost of ownership are central concerns.

Yet engineers found a way to push durability further without abandoning the gray iron family entirely. Boron-modified gray cast iron introduces a small but meaningful amount of boron, typically in the range of 0.03 to 0.08 percent. That tiny alloying addition does not revolutionize chemistry by itself, but it has a pronounced effect on surface hardness and overall wear resistance. The resulting material maintains the favorable thermal properties of gray iron while presenting a harder, more robust surface under the contact and friction experienced during engine operation. In high-performance and heavy-duty engines, boron-modified cast iron can extend service life in situations that push the envelope of load, temperature, and lubrication quality. The improvement translates into lower risk of micro-wear progression, reduced piston skirt scuffing, and more consistent piston movement over time. In practical terms, boron-modified irons help engines retain compression and efficiency longer, especially under demanding operating conditions where maintenance intervals might be tightened or where fuel quality and lubrication are variable.

Beyond gray iron and its boron-enhanced variant, the cast iron family includes other specialized forms designed for particular demands. Ductile, or nodular, cast iron introduces graphite in a spherical form, which increases tensile strength and toughness without sacrificing the wear resistance that makes iron-based sleeves viable. This toughness translates into higher toughness margins under thermal stress and the potential to tolerate minor misalignments or manufacturing tolerances without catastrophic failure. Alloyed cast irons, which incorporate chromium, molybdenum, or other carbide-forming elements, can offer improved hardness, corrosion resistance, or elevated temperature performance. These variants enable engine designers to tailor a sleeve’s behavior to a specific application, such as high-load industrial engines or engines operating in challenging cooling regimes. The through-line is clear: shaping the microstructure of cast iron through microalloying and microstructure control allows for a more resilient surface while preserving the favorable bulk properties that make cast iron economical and reliable.

While cast iron remains a stalwart, modern engineering increasingly considers lightweight alternatives to reduce parasitic weight and improve thermal efficiency. Aluminum alloys, for instance, have gained traction as sleeve materials in contemporary engines. Aluminum offers a favorable weight reduction and higher thermal conductivity, which can support faster heat transfer from the bore to the cooling system. In engines designed around aluminum sleeves, the aim is to leverage the metal’s natural heat-dissipating capability to keep piston temperatures in a wider operating envelope and to lower overall engine weight. However, aluminum does not inherently possess the same wear resistance and load-bearing characteristics as traditional gray iron, especially under high-load, high-mileage conditions where lubrication quality may vary or where combustion processes impose transient spikes in pressure. As a result, aluminum sleeves commonly rely on a precise balance of design strategies: coatings to reduce wear, optimized bore finishes, and in some cases, composite multilayer approaches that place an aluminum substrate behind a hard, wear-resistant surface. The shift toward aluminum sleeves is a reflection of a broader industry trend toward lighter components that can improve fuel efficiency while maintaining the durability expected in modern engines.

Steel, too, makes appearances in high-performance applications. When engines demand enhanced strength, hardness, and resistance to deformation at elevated temperatures, steel sleeves are an option. The steel variants employed for sleeves are typically selected for their hardness and ability to stand up to aggressive contact with pistons, especially in racing or heavy-duty contexts. This category often includes carbon steels and stainless or precipitation-hardening steels, chosen for their ability to hold tight tolerances, resist micro-wear, and tolerate aggressive thermal cycling. The tradeoffs are real: steel sleeves can be more challenging to machine, and their thermal expansion behavior may diverge from that of the surrounding cast iron or aluminum blocks if not matched carefully. For a designer, the choice to use steel hinges on a calculation of strength margins, cutting and finishing capabilities, and the need for sustained performance under boundary conditions that would degrade conventional iron sleeves. In practice, steel sleeves tend to appear in limited, high-stress segments of the market, where performance gains justify the added complexity and cost.

Ceramic and copper alloys are among the more specialized options. Ceramics, with their exceptional hardness and temperature resistance, offer very low friction coefficients and minimal wear in some high-temperature scenarios. Copper alloys, meanwhile, can deliver favorable tribological properties in systems where low friction and distinctive thermal characteristics are prioritized. These materials are not mainstream because they bring cost, manufacturing complexity, and maintenance considerations that place them in niche applications. When they do appear, they are typically tuned to engines with strict thermal management constraints, unusual lubrication regimes, or extreme operating temperatures. In those contexts, a ceramic or copper-based sleeve can enable extended service life where conventional iron or aluminum options would struggle.

Designers choose sleeve materials through a careful synthesis of expected load profiles, lubrication quality, and cooling strategy. The balance of wear resistance, thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance, and machinability must align with how the engine is built and used. A core consideration is the distinction between dry sleeves and wet sleeves. In a dry-sleeve arrangement, the sleeve remains a fixed bore of the engine block and encounters oil through the piston rings and oil films that brief the contact interface. In a wet-sleeve arrangement, the sleeve is in direct contact with cooling water or coolant, demanding even more robust corrosion resistance and stable dimensional behavior under thermal cycling. Cast iron, with its robustness and heat-handling capacity, has historically proven flexible across both configurations. Aluminum sleeves, when used in wet or dry settings, rely on precise thermal expansion compatibility and protective coatings to mitigate wear and ensure long life. Steel sleeves, with their high hardness, fit well in high-load wet-sleeve contexts where the engine must withstand aggressive pulsing loads. Each material choice is reinforced or constrained by the engine block’s geometry, the piston ring seal geometry, and the lubrication regime that the engine designer can rely on throughout its service life.

Manufacturing realities also guide the material choice. Casting processes readily produce the complex shapes required for sleeves, and gray cast iron’s machinability keeps production costs favorable for mass-market engines. In contrast, boron-modified-gray irons and ductile irons demand more controlled melting and alloying steps, yet they can still be produced at scale with modern foundry practices. Aluminum sleeves require different forming routes, such as casting or extrusion followed by precise heat treatment to achieve the necessary microstructure and surface hardness. Surface finishing, coatings, and heat treatments play a pivotal role in dictating wear behavior and lubrication compatibility. A common approach involves applying a surface treatment or coating that lowers the friction coefficient, reduces adhesive wear, and provides a robust interface with the piston rings. In engines with tight tolerances and high RPM, coatings can be essential to prevent early wear and to sustain consistent compression.

From a lifecycle perspective, re-sleeving an engine or replacing worn sleeves highlights another dimension of material choice. Gray iron sleeves, due to their toughness and predictable wear patterns, tolerate re-sleeving processes well and can often be refurbished with a new bore finish to restore performance. Boron-modified variants likewise support refurbishments, though the process must preserve the integrity of the hardened surface and the underlying microstructure. Aluminum sleeves, given their different thermal and mechanical properties, require careful assessment for reworkability. In some cases, engine designers design sleeves with modularity in mind, allowing the liner to be replaced without a complete engine block overhaul. This modular approach aligns with maintenance practices across industrial and automotive sectors, where downtime costs are significant and reliability is paramount. The eventual recycling and end-of-life considerations also come into play. Cast iron components are widely recyclable, aligning well with circular economy principles. Aluminum sleeves, while lighter and energy-intensive to produce, offer high recyclability as well. The broader material choices thus intersect with environmental considerations, a factor that modern engine programs increasingly weigh alongside performance and cost.

The broader takeaway from the material landscape is that cast iron—especially gray iron and boron-modified gray iron—continues to be a dominant driver of durability and cost-effectiveness in many engines. Their performance under high temperatures, their damping attributes, and their compatibility with standard manufacturing practices keep them front and center. Yet the push toward lighter, thermally efficient designs means aluminum sleeves are rising in relevance, especially where fuel economy targets drive design decisions. In extreme-duty or high-performance contexts, steel sleeves or specialized alloys offer a hedge against extreme loads and temperatures, albeit with greater manufacturing and maintenance considerations. And for exceptionally demanding or niche applications, ceramic or copper-based sleeves provide tradeoffs that some engineers are willing to accept in exchange for specific friction or temperature advantages.

This material conversation, while technical, reveals a fundamental truth about engine design: every choice about a sleeve’s material reverberates through the engine’s thermal, mechanical, and lubrication systems. The sleeve does not exist in isolation. Its properties influence heat transfer efficiency, the stability of compression, the rate at which wear accumulates on the piston rings, and how readily the engine can retain performance over its service life. The art lies in matching the sleeve material not only to the engine’s power and torque profile but also to the maintenance realities of the vehicle or equipment, the quality of available lubricants, and the environmental conditions in which the engine runs. The research landscape underscores that this is a field of purposeful compromise rather than a quest for a universal solution. Each material family offers a distinct set of advantages, and the best choice is the one that aligns with a project’s specific goals: cost, durability, weight, thermal management, and lifecycle feasibility.

To close the loop on the material spectrum and to anchor this discussion in practical terms, consider how a designer might approach a new engine variant. The decision begins with load and heat expectations. If the engine will operate in a hot, heavy-duty environment with aggressive duty cycles, gray iron’s cemented balance between wear resistance, heat dissipation, and manufacturability makes it an attractive baseline. If the design aims to reduce weight and improve cooling efficiency without stepping away from proven wear performance, aluminum sleeves—paired with coatings and optimized gland design—offer a compelling path, provided the lubrication strategy is tightly controlled. If the engine targets extreme performance conditions—think racing or high-load industrial machinery—the option to deploy hardened steel or specialized alloys may be pursued, with an eye toward manufacturing capability and the long-term maintenance plan. In a few very specialized cases, ceramics or copper alloys might be selected for their low friction or exceptional heat resistance, recognizing that such choices demand careful consideration of manufacturing, coating technology, and service logistics.

The materials story for engine cylinder sleeves, then, is not a simple catalog but a spectrum that reflects the engine’s mission. Cast iron, in its gray and boron-modified forms, remains the backbone of reliability and cost efficiency. Aluminum is the aspirational middle ground for weight and heat handling. Steel and exotic variants act as the high-performance options for extreme duty, while ceramics and copper alloys supply niche advantages where tribology and high-temperature stability are non-negotiable. This spectrum is not merely about material science; it is about engineering a coherent system where the sleeve’s behavior harmonizes with piston dynamics, lubrication regimes, cooling capacity, and serviceability. The chapter on materials thus threads together mechanical properties, manufacturing realities, and lifecycle considerations to reveal how a sleeve’s material identity extends far beyond a surface finish or a bore diameter. It shapes a machine’s reliability, its maintenance footprint, and ultimately its value across a vehicle’s or a machine’s working life. For readers seeking a concise primer on engine sleeves and their roles, the explainer linked earlier offers a solid starting point that complements this broader materials-focused chapter.

External resource for deeper reading: https://www.sae.org/

Aluminum Alloy Sleeves: Lightweight, Thermally Smart Solutions for Modern Engine Cylinders

Aluminum Alloy Sleeves: Lightweight, Thermally Smart Solutions for Modern Engine Cylinders

Aluminum alloys have reshaped how engineers approach cylinder sleeve design. Their low density and high thermal conductivity give clear advantages where weight and heat control matter most. Modern engines demand smaller displacement, forced induction, and tighter packaging. In that environment, every kilogram saved and every degree of temperature better managed yields measurable gains in fuel economy, emissions, and performance. Replacing or complementing traditional cast iron sleeves with aluminum-based solutions supports these goals while introducing new design freedoms.

A primary advantage of aluminum is its mass. Aluminum alloys weigh roughly one-third as much as steel or cast iron. Reduced reciprocating mass lowers overall engine weight and the inertia the crankshaft and bearings must overcome. For vehicles, lighter engines translate to lower fuel consumption and improved acceleration. Studies link a 10 percent vehicle mass reduction to a 6–8 percent drop in fuel use. That relationship makes aluminum a compelling choice for automotive programs focused on downsizing and electrification strategies.

Thermal management is another strong point. Aluminum alloys conduct heat two to three times better than cast iron. This helps spread combustion heat faster through the cylinder liner and into the cooling system. Better heat flow can reduce local hot spots, flatten temperature gradients, and lower thermal stresses in the block. The result is more consistent ring seating, reduced oil breakdown, and improved long-term dimensional stability. For turbocharged or high-specific-output engines, improved heat dissipation supports higher power density without shortening component life.

Yet aluminum also introduces challenges. Pure aluminum lacks the wear resistance of cast iron. Its softer matrix is prone to rapid surface wear when exposed to sliding contact under combustion loads. To overcome this, manufacturers and researchers developed hybrid approaches. One route places a harder insert inside an aluminum bore, combining aluminum’s lightness with a wear-resistant running surface. Another route employs advanced aluminum-silicon alloys, which form hard silicon particles in a softer aluminum matrix, creating a composite microstructure capable of resisting abrasion.

Hypereutectic aluminum-silicon alloys stand out among these options. With silicon contents typically in the range of 15–20 percent, these alloys crystallize with a network of hard silicon particles. Those particles act as a distributed hard phase, resisting scuffing and reducing the removal of material by piston rings and particulates. Hypereutectic compositions also lower thermal expansion compared to pure aluminum, improving bore stability during temperature swings. That reduced expansion helps maintain tighter clearances between pistons and cylinders, aiding compression and reducing oil consumption.

Manufacturing plays a decisive role in performance. Solid castings of hypereutectic alloys require controlled cooling to avoid coarse silicon particles and porosity. Advanced casting methods such as squeeze casting and semi-solid metal casting improve microstructure uniformity. Squeeze casting applies high pressure during solidification, minimizing voids and refining grain structures. Semi-solid processing reduces segregation and yields a thixotropic slurry that fills complex molds cleanly. In-situ techniques, where hard phases form during processing, also deliver finely dispersed particles that enhance wear resistance and toughness.

Beyond monolithic castings, composite and coated solutions broaden the design space. Aluminum blocks can be manufactured with thin steel or cast-iron liners. Those liners supply proven wear surfaces while aluminum provides the lightweight structure. Alternatively, aluminum bores can be coated with thermally sprayed ceramic or nickel-based layers. Plasma spraying and high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) methods deposit dense, adherent coatings that resist wear and scuffing. Achieving good bonding and low residual stress remains critical when adding a dissimilar layer to a thermally conductive aluminum base.

Tribological pairing is central to success. The running surface must work with ring metallurgy and lubrication strategies. Rings designed for aluminum sleeves often use special coatings and lower contact pressures to reduce wear. Lubricant formulation adapts as well, with additives that improve film strength at higher operating temperatures. The aluminum microstructure and coating selection inform ring profile, surface finish, and break-in procedures. Properly engineered, an aluminum-sleeved cylinder can match or exceed the longevity of cast iron when optimized as a system.

Thermal fatigue and galling risk are important concerns in aluminum sleeves. Repeated thermal cycling and concentrated contact stresses can produce microcracks or surface transfer. Hypereutectic alloys reduce the tendency, but attention to surface engineering and control of combustion dynamics remains essential. Designers mitigate risk through thicker wall sections where necessary, optimized coolant passages, and ring pack tuning to limit local heat generation. Engine management, including timing and boost control, also affects the thermal load and thus the sleeve’s durability.

Cost and manufacturability influence adoption. Aluminum alloys and their advanced casting or coating processes typically cost more than conventional cast iron sleeves. Initial tooling and precise process control add expense. However, lifecycle benefits can offset higher upfront costs. Reduced fuel use, improved vehicle packaging, and the ability to integrate complex cooling channels often justify the investment in higher-volume production. For high-value markets—lightweight vehicles, performance cars, and hybrid systems—the trade-off favors aluminum solutions.

Real-world use cases highlight where aluminum excels. Compact turbocharged engines benefit from lighter blocks and better heat rejection. Hybrid vehicles gain from reduced engine weight contributing to overall system efficiency. Stop-start systems and frequent engine cycling demand materials that warm and cool rapidly; aluminum’s thermal responsiveness fits this need. Importantly, aluminum enables closer integration between cylinder geometry and cooling paths, giving engineers the chance to redistribute material where strength and stiffness are necessary and remove it where only thermal conduction matters.

Serviceability and repairability also differ between material choices. Steel or cast-iron liners can be replaced, allowing overhaul shops to renew bores without replacing the entire block. Monolithic aluminum sleeves with specialized coatings may require different repair methods, such as re-plating or carefully controlled honing. For end-users and service networks, this can mean shifts in maintenance practices and tooling. Clear guidelines for in-service inspection, break-in, and component swapping help ensure long-term reliability.

Environmental considerations further support aluminum. Aluminum is highly recyclable without significant loss of properties. Using recycled content reduces embodied energy and greenhouse gas emissions tied to material production. When paired with lighter vehicle mass and improved fuel economy, aluminum sleeves contribute both to tailpipe emission reductions and to lower lifecycle environmental impact. That alignment is important for manufacturers targeting regulatory compliance and sustainability targets.

Looking ahead, incremental improvements continue. Nano-reinforcements, refined particle morphologies, and hybrid processing routes promise better combinations of weight, thermal performance, and wear resistance. New coating chemistries and laser surface treatments offer routes to stronger bonds and thinner, more durable running layers. At the systems level, integration with cylinder head cooling, variable valve timing, and combustion control will enable engines to push performance while keeping sleeves within safe thermal and mechanical limits.

For readers curious about cylinder sleeve basics and how aluminum fits among other sleeve materials, see the primer on what engine sleeves are and how they function. That resource explains core concepts and helps place aluminum alternatives in context: what are engine sleeves.

Empirical study supports the practical viability of hypereutectic aluminum sleeves. Research shows that properly cast and heat-treated Al-Si sleeves exhibit favorable microstructures and wear characteristics, especially when produced with controlled solidification methods. Those findings validate aluminum’s role in next-generation engines, provided manufacturing meets the required tolerances and surface engineering is aligned with ring and lubricant design.

Aluminum-alloy cylinder sleeves are not a blanket replacement for cast iron. Instead, they represent a strategic material choice. When light weight, rapid heat transfer, and recyclability are primary objectives, aluminum-based solutions offer distinct benefits. When extreme durability under harsh duty cycles remains paramount, traditional materials or hybrid liners still play a role. The most successful designs balance these trade-offs, using aluminum where it maximizes system value and pairing it with inserts, coatings, and process controls to ensure long-term performance.

External technical validation and detailed microstructural analysis of hypereutectic Al-Si sleeves, including data from squeeze casting trials, appear in the literature. For a focused study on microstructure and wear behavior of hypereutectic Al-Si alloy cylinder sleeves made by squeeze casting, consult this peer-reviewed article: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092150932300054X

Forged Steel Sleeves in Motion: The Steel Case for High-Performance Cylinder Liners

When engineers push engines toward greater power, efficiency, and durability, every component is scrutinized for its contribution to reliability under stress. Among the stack of decisions, the choice of material for the cylinder sleeve stands as a decisive factor. In high-performance applications, steel sleeves are favored not for the casual run of a modern daily vehicle, but for turbocharged, high-compression, or demanding duty cycles where temperatures spike, loads soar, and long-term stability matters as much as peak strength. The conversation around what material sits inside the engine block is not merely one of weight or cost; it is a careful balancing act among mechanical properties, heat management, wear resistance, and the ability to tolerate dynamic, extreme operating environments. Steel, in this context, is not a single monolithic material but a family of high-strength ferrous alloys designed to maintain structural integrity where softer, more common sleeve materials might falter. In that sense, the steel sleeve becomes the backbone of a power plant that must survive repeated throttle applications, rapid load changes, and the thermal cycling inherent to forced induction or aggressive fueling strategies. The broader article on cylinder-sleeve materials begins with the recognition that cast iron and aluminum alloys each have their places in the spectrum of engine design. Cast iron remains the workhorse for many production engines due to affordable wear resistance and thermal stability. Aluminum sleeves, particularly when integrated with aluminum blocks or sophisticated cooling schemes, offer weight reduction and faster heat transfer. Yet when the design targets extreme reliability under demanding temperatures and mechanical loads, steel stands out for its ability to resist deformation, maintain circularity, and support extended service life under fatigue-prone conditions. This chapter traces why steel sleeves become the preferred choice in high-performance contexts and how engineers tailor their properties to meet the exacting demands of turbocharged and high-compression engines, while also considering manufacturing realities and installation techniques that enable consistent, repeatable performance over thousands of hours of operation. At the heart of this decision is the recognition that steel alloys can be engineered to combine high tensile strength, toughness, and surface hardness with resistance to creep and cracking as temperatures rise. The cylinder bore is not merely a hollow space; it is a dynamic interface where piston rings, lubrication films, and thermal gradients interact. In a turbocharged scenario, peak cylinder pressures can dwarf those found in naturally aspirated designs, and the cycle-to-cycle variation in temperature becomes a critical factor. A steel sleeve can resist the kind of plastic deformation that would widen a bore under high loads, preserving a stable bearing surface for the piston rings. The increased stiffness of steel sleeves translates into less bore distortion during bursts of power, which, in turn, helps maintain optimal sealing between rings and cylinder wall. That sealing is not a trivial matter. Engine wear begins where metal-to-metal contact can occur, and elevated heat can accelerate that wear. A sleeve with a robust steel matrix resists micro-welding and scuffing even when lubrication films momentarily thin out under rapid acceleration or high RPM. This hard-wearing performance does not come at the expense of thermal behavior, either. While steel generally conducts heat less aggressively than aluminum, the right steel alloy can still dissipate heat efficiently enough to prevent hot spots from becoming bottlenecks in performance. A well-designed high-strength steel sleeve is paired with a carefully chosen block material, an optimized jacket cooling system, and precise bore finishing to achieve a synergy where heat is managed without sacrificing structural integrity. The result is a bore that remains round and true, even after tens of thousands of miles of spirited driving or long-haul, high-load operation. The discussion of steel sleeves in this context also highlights a core manufacturing truth: achieving the precise inner diameter, straightness, and surface finish required for high-performance use depends on controlled processing, heat treatment, and joinery methods that preserve a consistent microstructure. The sleeve may be formed from forged steel or other high-strength ferrous alloys and then treated to achieve a hard, wear-resistant surface while retaining toughness in the core. The grain structure, refined during forging, contributes to improved fatigue resistance, especially under cyclical loading. The residual stresses introduced during forging and subsequent finishing help the sleeve resist deformation when subjected to the temperature swings that accompany throttle changes and burning fuel. In high-performance engines, precision is not decorative. It is the engine’s lifeline; any deviation from an optimal bore roundness or surface finish can alter piston-ring dynamics, friction, and oil control. The bearing surface must sustain an oil film that can separate metal surfaces while distributing wear evenly. Steel sleeves can be engineered to accept various surface finishing approaches—polished, cross-hatched, or plated in a way that harmonizes with the chosen piston rings and lubrication regime. The latter is not a separate afterthought; it is an integral part of the sleeve’s design. Surface hardness, often achieved through carburizing, nitriding, or other case-hardening processes, creates a wear-resistant shell that stands up to the abrasive action of ring contacts. This surface layer also provides a protective barrier against corrosive byproducts that may form at high combustion temperatures. Corrosion resistance remains a consideration, particularly in engines that experience variable cooling efficiency or those that operate in harsh environments. The steel sleeve’s alloy composition can be tailored to resist oxidation and chloride-induced corrosion, ensuring that the bore’s integrity is not compromised by aggressive fuels, additives, or ambient conditions. The physics of heat transfer complicates this story, but it does not derail it. In a high-performance engine, the sleeve must participate in heat dissipation without becoming a bottleneck. Steel’s specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity, while not as favorable as aluminum, can be balanced with a cooling strategy designed to remove heat efficiently from the combustion chamber. This often involves a combination of optimized cooling channels, oil cooling, and, in some designs, targeted thermal coatings that reflect radiant heat away from the bore. Each design choice—whether to use a steel sleeve, which alloy to select, and how to treat the inner surface—reflects a system-level optimization. It is not enough for a sleeve to be strong; it must be compatible with pistons, rings, lubricating oil, and the engine’s overall thermal and mechanical cycle. The compatibility extends to assembly practices. In many high-performance builds, sleeves are installed with an interference fit, which creates a tight mechanical lock that resists creeping or loosening under load. The interference fit reduces the risk of slip between the sleeve and the block or crankcase, maintaining bore position and concentricity. The interference fit also minimizes movement between components during high-torque transients, preserving piston ring sealing and reducing the likelihood of scuffing or scuff-induced oil consumption. In some cases, manufacturers employ friction welding to join forged steel sleeves with other steel components, creating a unified, robust assembly. Friction welding produces a symmetric, bore-friendly joint that preserves the sleeve’s interior geometry and eliminates gaps that could complicate oil film formation. The goal is to ensure a clean, rigid interface that facilitates predictable thermal and mechanical behavior under extreme conditions. The installation process and tolerance control are as critical as the material selection itself. When a sleeve is pressed into the block, precise bore alignment and surface finish must be achieved so that the ring pack can seat correctly and oil rings can establish a stable oil film. In high-performance contexts, tolerances are tightened to guarantee smooth rotation of the piston and balanced contact pressures across the ring pack. Any misalignment can translate into rapid wear, elevated oil consumption, or noisy operation. The engineering approach to steel sleeves in performance applications also includes the ability to tailor sleeves for specific cylinders and cranktrain configurations. Sleeve geometry may be adapted to accommodate different crank throws or to align the sleeve’s inner surface finish with alternate piston-ring materials and coatings. This tailoring is part of a broader philosophy: the sleeve is not a one-size-fits-all part but a component whose microstructure and macro geometry are tuned to the engine’s expected duty cycle. The discussion is not complete without acknowledging the practical realities that accompany the use of steel sleeves. While they deliver extraordinary performance, steel sleeves come with higher material costs, more demanding machining, and longer lead times for manufacturing and inspection. The benefits—superior wear resistance, deformation resistance under heat, and predictable behavior under high load—must be weighed against these economic considerations. In many racing or aerospace contexts, the additional expense is justified by longer service life and reduced downtime, which translates into higher effective reliability and performance. For a reader who wants to understand the practical implications of steel sleeves in more detail, a broader explanation of sleeved engine blocks can be found here: sleeved engine block explained. This reference helps connect the material science behind the sleeve to the real-world assembly, maintenance, and inspection practices that keep high-performance engines reliable under demanding usage. As this chapter has shown, the steel sleeve’s appeal in high-performance contexts rests on a trifecta of material science, manufacturing sophistication, and installation precision. The intersection of alloy chemistry, surface treatment, and an accurate fit within the engine block creates a bore that can resist deformation, maintain seal integrity, and endure the heat of repeated high-pressure cycles. It is a reminder that in engine design, the choice of sleeve material is not an isolated decision; it is a strategic element of a broader performance architecture. The sleeve’s robustness must be matched by compatible piston rings, compatible lubrication strategies, and an effective cooling regime. When these elements align, steel sleeves provide a stable platform for sustained high performance, enabling engines to endure the rigors of forced induction, high compression, or extended operation at high RPM without compromising accuracy or reliability. The result is a powertrain that remains predictable as temperatures rise, load demands increase, and the engine faces a future of continued high-performance ambition. For readers seeking deeper technical insights into forged steel sleeve cylinders, including composition, standards, and applications, the following external resource offers a detailed synthesis: Understanding Forged Steel Sleeve Cylinder: Composition, Standards, and Applications. https://www.boberry.com/blog/understanding-forged-steel-sleeve-cylinder-composition-standards-and-applications

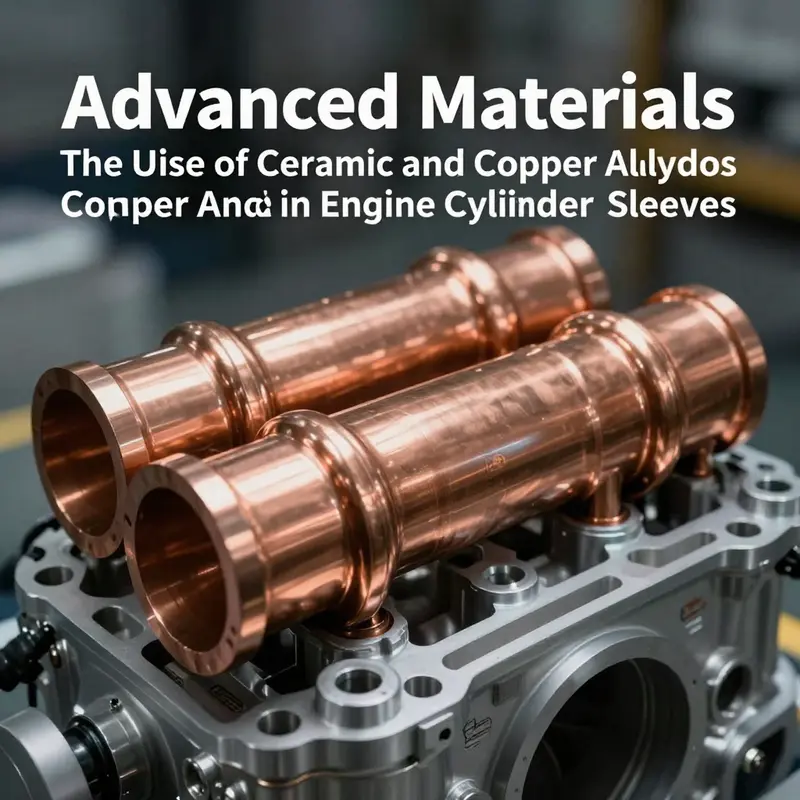

Hybrid Heat Control: How Ceramic Coatings and Copper Alloys Transform Cylinder Sleeves

Engine cylinder sleeves face relentless mechanical and thermal stress. Choosing sleeve material shapes engine life, efficiency, and service needs. Traditional cast iron and steel remain common. Yet advanced applications increasingly rely on ceramic coatings and copper alloys. Together they form hybrid solutions that balance heat flow, wear resistance, and manufacturability. This chapter explores how these materials work alone and in combination, why engineers choose them, and what their trade-offs mean for real engines.

Ceramic coatings have earned a place in high-performance and heavy-duty engines because they change how a combustion chamber handles heat and friction. Applied as thin, engineered layers, ceramics act as protective shields. They resist the abrasive action of piston rings and combustion particles. They maintain mechanical stability at elevated temperatures. They also alter thermal gradients inside the cylinder. Some ceramic systems are designed as thermal barriers, reducing heat transfer to the block. Others focus on low friction and wear, keeping running clearances tighter and reducing oil consumption. The result is a sleeve surface that endures higher loads and longer service intervals.

Manufacturing techniques determine ceramic performance. Plasma spraying is common because it deposits robust layers quickly. Physical vapor deposition and thermal spraying can create dense, adherent coatings with controlled microstructures. Laser surface texturing pairs with these coatings to introduce micro-features. These features help distribute lubricant, trap debris, and reduce direct metal-to-metal contact. The combination of a textured surface and a ceramic topcoat can lower friction and improve oil film stability. That means less wear and more consistent performance under transient loads.

Ceramics used for cylinder surfaces are chosen for hardness, wear resistance, and thermal stability. Oxide ceramics and nitride ceramics are typical choices. They offer high hardness and resistance to chemical attack from combustion byproducts. A downside is brittleness. Without careful design, a ceramic layer can crack under shock or poor adhesion, causing rapid deterioration. Engineers therefore focus on adhesion methods, graded interfaces, and post-deposition treatments to reduce the risk of delamination. Proper bonding and appropriate substrate preparation are essential for long-term service.

Copper alloys bring a complementary set of advantages. Their standout property is thermal conductivity. Copper moves heat away from the combustion zone efficiently. In a sleeve design, a copper-based layer or insert can rapidly conduct peak heat into the cooling system. That reduces local thermal spikes and helps control piston and ring temperatures. Copper alloys also machine well, enabling tight dimensional control during manufacture. For custom or repaired sleeves, machinability allows precise fit and finish, which benefits sealing and ring seating.

When combined, copper and ceramic deliver a hybrid function. A copper base acts as a heat sink, while a ceramic top layer handles surface wear and friction. This pairing allows the engine to operate at higher outputs without over-stressing the block. It also improves thermal management in dense or turbocharged engines, where local hot spots can otherwise cause knock or material fatigue. The key is balancing ceramic insulation and copper conduction. Too thick a ceramic layer defeats the copper’s cooling role. Too thin a ceramic layer sacrifices wear protection. Engineers therefore tailor layer thickness and microstructure to the engine’s duty cycle.

Practical implementations vary. Some sleeves use a copper-rich core clad with a thin ceramic layer applied by plasma spray. Others employ copper matrix composites with ceramic particulates dispersed in the metal. These composites combine conductivity with enhanced wear resistance. Functionally graded materials are another approach. They gradually change composition from copper at the core to ceramic at the surface. This gradient reduces thermal and mechanical mismatch, improving adhesion and reducing the risk of cracking under thermal cycling.

Compatibility with the engine block and cooling system matters. Copper’s thermal expansion differs from aluminum and cast iron. If not accounted for, these mismatches create stresses during temperature changes. Designers often add intermediate layers, use compliant bonding agents, or design mechanical fits that accommodate expansion. Corrosion behavior also requires attention. Copper alloys can be susceptible to certain corrosion mechanisms in specific coolant chemistries. Proper coolant selection and corrosion inhibitors remain important when copper components are present.

The benefits of hybrid ceramic-copper sleeves are tangible. Engines gain improved thermal control and reduced wear at the piston/sleeve interface. Lower friction translates to incremental fuel savings. Better heat dissipation reduces thermal fatigue and can extend time between overhauls. In specialty fields such as motorsports and aviation, these gains translate into higher power density and more predictable performance under extreme conditions. For industrial engines, they mean longer service life and reduced downtime.

However, advanced materials come with trade-offs. Cost is the most obvious. Ceramic deposition and copper alloy fabrication demand specialized equipment and skilled labor. Repair procedures are more complex than simple sleeve replacement. In the event of coating failure, restoration often requires stripping and reapplication under controlled conditions. In-situ repair options exist, but they need careful evaluation.

Maintenance and inspection regimes also change. Non-destructive testing becomes more critical. Techniques such as ultrasonic inspection, eddy current testing, and adhesion pull tests detect subsurface delamination or micro-cracks before catastrophic failure. Tribological testing under representative conditions validates coating behavior with the selected piston rings and oils. Thermal cycling tests simulate decades of operation in accelerated time. These tests protect against premature field failures and inform refurbishment schedules.

Sustainability and restoration benefit from advanced coatings as well. Cylinder liner restoration technologies now enable re-coating and reconditioning of sleeves regardless of the original base material. This reduces the need for full sleeve replacement or block swaps. It also extends the useful life of engine blocks that would otherwise be scrapped. For fleets, the economics can favor refurbishment with advanced coatings, because downtime and part cost are reduced compared to complete replacement.

Designers must weigh performance gains against manufacturing complexity. For example, achieving consistent coating thickness and bond strength across many cylinders in a production engine demands stringent process control. High-volume manufacturing may prefer simpler solutions, such as cast iron liners or integrated aluminum bores with cast-in inserts. But as manufacturing methods mature, adoption of hybrid sleeves will broaden. Additive manufacturing and improved deposition systems are already reducing costs and improving repeatability.

Future directions point to even more integration between materials science and surface engineering. Nanoscale reinforcements and hybrid particulate systems will further tune wear and thermal properties. Surface textures will be optimized to retain lubricant under higher loads. Functionally graded interfaces will become standard practice to reconcile thermal expansion differences. In addition, advances in coolant chemistry and lubrication will allow engineers to push ceramic-coated copper sleeves harder without sacrificing longevity.

Selecting the right sleeve material always depends on the engine’s requirements. For a long-lived industrial diesel, wear resistance and reparability may top the list. For a racing engine, thermal control and low friction may dominate. For a mass-market passenger vehicle, cost and manufacturability usually win. Hybrid ceramic-copper solutions shine where performance and longevity justify their complexity. They offer a tailored balance of conduction, insulation, and wear resistance that no single traditional material achieves alone.

To understand these materials in the wider context of engine sleeves, consult clear overviews that explain sleeve types and functions. A useful internal resource explains core sleeve concepts in practical terms: what are engine sleeves. For research and advanced reading, recent academic work details the latest composite and coating strategies. These sources show how ceramic top layers over thermally conductive bases are evolving as real-world solutions. They also highlight the testing and process controls that underpin reliable deployment.

The takeaway is straightforward. Ceramic coatings and copper alloys are not silver bullets. They are tools that, when combined thoughtfully, enable engines to run hotter, cleaner, and longer. Their strengths are complementary: copper moves heat away fast, while ceramics resist wear and lower friction. Managing their interaction requires careful design, precision manufacturing, and rigorous quality control. When those elements align, hybrid sleeves offer a compelling path to greater engine performance and durability.

Further reading: Advanced Materials article

Final thoughts

Understanding the materials used in engine cylinder sleeves is vital for anyone involved in motorcycle or auto ownership and maintenance. From the cost-effective and reliable cast iron options to high-tech aluminum alloys, performance-oriented steel, and advanced ceramics, each material serves distinct purposes and impacts engine performance. As repairs and modifications continue to evolve, staying informed about these materials can not only extend the life of your vehicle but also optimize its performance. Always consult with professionals for tailored advice relevant to your specific engine and driving needs.