PACCAR’s MX-11 and MX-13 family power a wide range of Kenworth and Peterbilt heavy-duty applications. A defining engineering choice in these engines is whether the cylinders use removable wet sleeves or an integrated, non-sleeved wall. The MX engines employ a parent bore block design, where the cylinder walls are an intrinsic part of the cast iron block rather than separate sleeves. That choice influences heat management, stiffness, service routines, and rebuild options, with clear implications for owners, repair shops, and parts distributors. In the following sections, we connect the cylinder design to practical realities: how the absence of traditional sleeves shapes material choices and manufacturing, what this means for in-frame maintenance and overhauls, how it affects performance and emissions, and what fleets should consider when budgeting for lifecycle maintenance. Each chapter builds on the central question of sleeved versus sleeveless cylinder design, translating engineering decisions into actionable guidance for motorcycle and auto owners, repair facilities, and parts suppliers who deal with PACCAR-powered platforms.

Sleeve or Solid: Do PACCAR MX Engines Have Sleeved Cylinders?

Answer: PACCAR MX engines predominantly use a parent bore cylinder block design, where the cylinder walls are part of the block rather than traditional wet sleeves. This provides stiffness and consistent head gasket sealing under high-pressure, high-temperature operation. However, sleeves do exist in the MX ecosystem as serviceable interfaces rather than as the primary cylinder wall. In particular, injector sleeves are replaceable components that support injector seating and sealing, and may be replaced during in-frame maintenance without a full block overhaul. If cylinder wear becomes excessive, overhauls may require reboring and the installation of repair sleeves or, in some cases, a block replacement. So, while PACCAR MX engines are not built around traditional wet sleeves for the cylinder walls, sleeve elements especially injector sleeves, play a practical maintenance role. For general background on engine sleeves, see resources such as What are engine sleeves? https://itw-autosleeve.com/blog/what-are-engine-sleeves/.

Sleeved Cylinders or Solid Walls: Reexamining PACCAR MX Engine Cylinder Design and Its Maintenance Implications

The question at the heart of this chapter—do PACCAR diesel engines have sleeved cylinders?—is more nuanced than a simple yes or no. It sits at the intersection of engineering tradition, manufacturing choices, and the realities of fleet maintenance. In the world of heavy‑duty trucking, the answer depends on who you ask and which variant, year, or service manual you consult. The material you encounter can feel contradictory at first glance: some sources describe a traditional, non‑sleeved, parent‑bore block; others point to sleeved cylinders that invite liner replacement as a straightforward service event. What follows is not a verdict imposed from on high, but a cohesive reading of the available evidence, the engineering logic behind each approach, and the practical consequences for maintenance planning and lifecycle costs in real fleets.

To begin, a core distinction must be understood. Sleeved cylinder technology relies on replaceable cylinder liners, a concept familiar to many heavy‑duty engines. Wet sleeves sit in direct contact with coolant and can be rebuilt by replacing worn liners, which avoids machining the core block itself. Dry sleeves, by contrast, are fixed into the block and aren’t in direct coolant contact. The sleeve approach can simplify in‑frame maintenance and extend block life because a worn surface can be refreshed without a complete block replacement. This is especially valuable for engines operating at high temperatures and pressures, in environments where high boost and stringent emissions controls push cylinder pressures upward. In the broader industry, sleeves have long been a standard tool for durability and rebuildability, even as designs push toward lighter, stiffer blocks.

Within the PACCAR MX family—long a staple in Kenworth and Peterbilt heavy duty applications—the literature presents two vectors of thought. One prevailing narrative, reflected in engineering summaries and some aftermarket commentary, emphasizes a “parent bore” block design. In this scenario, the cylinder walls are integral to the cast iron block, machined to precise dimensions without removable liners. Advocates of parent bore argue that such a design yields greater block stiffness, a factor that benefits head gasket sealing under high cylinder pressures. They also contend that a more straightforward coolant pathway and reduced cavity complexity can improve thermal management, potentially aiding emissions compliance and reducing some manufacturing costs. From a certain angle, the parent bore approach aligns with a broader industry trend toward structural rigidity, weight optimization, and streamlined production processes—an approach that often trades the convenience of in‑frame sleeve wear‑surfaces for the benefits of a lighter, more compact, and thermally efficient architecture.

However, the technical literature also presents a different, equally plausible picture. There are credible indications that, at least for some PACCAR MX variants, sleeved cylinders are employed. The cylinder liner can be a critical, replaceable wear surface engineered from high‑grade cast iron or other wear‑resistant alloys. In engines where sleeves are used, the liners can be replaced individually when wear or damage occurs, supporting longer overall engine life when the rest of the block remains sound. This approach gains appeal in heavy‑duty applications where downtime is costly and the ability to perform targeted repairs without a full block overhaul is a strong economic and logistical consideration. Liner materials in such designs are selected for wear resistance, thermal conductivity, and resistance to scuffing under high compression and heat—a practical choice for engines that routinely operate under heavy loads and demanding duty cycles.

The conflicting signals about PACCAR MX cylinder walls in the provided research materials underscore a familiar truth in modern engine architecture: manufacturers continually refine block concepts, and the exact configuration can vary by model year, production run, or market. In the MX‑13 specifically, the sleeve narrative appears with evidence pointing to a design in which cylinder liners—whether for wear management or thermal performance—play a central role in the combustion chamber environment. The materials commonly cited for liners in this context include high‑grade cast iron and specialized alloys that balance wear resistance with efficient heat transfer. The durable operation of a high‑output diesel in constant duty cycles hinges on this balance, where even small gains in liner material properties or surface finishing can translate into meaningful extensions of service life and maintenance windows.

Yet the practical implications for a maintenance practitioner or fleet manager demand a sober appraisal of how these designs alter in‑frame overhauls. In a sleeved engine, in‑frame work can often be accomplished by replacing liners or repairing liners with suitable sleeves, a process that preserves the block as the fundamental structure. In contrast, a parent bore design—if the cylinder walls are truly integral and do not use removable liners—tends to push the maintenance strategy toward reboring and installing repair sleeves or, when wear exceeds tolerances, more extensive block replacement. The economic calculus here is nuanced. While a parent bore block can deliver benefits in stiffness and streamlined coolant flow, the inability to easily refresh worn cylinders via a simple liner swap can lead to longer downtimes and greater material costs when robust overhauls are needed.

Where this becomes especially salient is in how fleets plan for the long horizon. Operators accustomed to the modular replacement of sleeves may confront a different cost and downtime profile when a non‑sleeved block is involved. When a cylinder scores or wears beyond specification in a parent bore setup, the decision often shifts toward machining to an oversized bore and fitting a custom piston or resorting to installing repair sleeves—both options that require specialized equipment, precise alignment, and experienced technicians. Conversely, a sleeved configuration enables a more segmented maintenance rhythm: the sleeves can be swapped or honed as a discrete maintenance item, and the engine can return to service with minimal disruption to the block’s core integrity. This is not to diminish the durability of parent bore blocks, but it is to acknowledge that the maintenance ecology changes with the chosen geometry.

On the engineering side, the evidence in the gathered sources also points to the broader benefits that designers seek in modern PACCAR engines. The parent bore approach’s tighter control over cylinder wall finish, surface treatment, and thermal loading can contribute to predictable oil film retention and precise piston ring sealing. In high‑output, emissions‑constrained engines, the refinement of cylinder wall geometry and coatings is not a luxury but a necessity for maintaining tight tolerances under thermal cycling and pressure fluctuations. Alongside this, the overall block design—whether it leverages a parent bore or a linered approach—interacts with heat management strategies, coolant routing, and the durability of head gaskets under heavy loads. The result is a well‑engineered balance: a design that supports strong emissions compliance, structural stability, and efficient heat removal, but with different maintenance implications depending on whether liners are in play.

From a materials science perspective, the debate also reflects a practical reality: optimizations in wet sleeves, dry sleeves, and non‑sleeved blocks aim to optimize a complex set of criteria. The cylinder liner’s role as a wear surface, a heat conductor, and a barrier against gas leakage makes its material choice crucial. In sleeved MX configurations, liners must resist scuffing, maintain oil film integrity, and endure repeated thermal expansion and contraction cycles. In parent bore designs, the integrity of the bore surface and the quality of the honing process take on enhanced importance because the surface is not conveniently replaceable. In both cases, manufacturers invest in tight process controls—genius in honing, casting, and finishing—to ensure consistent oil film behavior, piston ring sealing, and lubrication distribution. These are not cosmetic refinements; they are the underpinnings of durability and performance at the extremes of heavy‑duty operation.

For readers seeking a concise orientation to the concept of sleeves, the industry resource base offers accessible explanations that underscore how sleeves function within an engine block. If you want a deeper dive into what engine sleeves are and how they affect maintenance planning, see what are engine sleeves. This contextualizes the sleeve option as one of several design tools engineers can deploy to balance serviceability with performance. It also helps explain why a sleeved configuration might be equally valid in a PACCAR MX context, depending on the exact block design and the intended maintenance strategy. As with so many categorizations in engineering, the most honest answer is nuanced: the MX family can be discussed in terms of sleeves or non‑sleeved blocks, but the precise implementation depends on the specific variant and its lifecycle backstory.

The external scaffolding of this discussion is reinforced by contemporary industry descriptions and catalog notes that reflect the ongoing evolution of PACCAR’s cylinder technology. In the MX‑13, an architecture that emphasizes durability and efficiency under load can be seen as compatible with a sleeved approach, especially when the target is high‑duty reliability and critical emissions performance. Yet, other sources emphasize a parent bore concept, highlighting stiffness and streamlined cooling as design priorities that serve the same end goals from a different mechanical pathway. Rather than declaring one correct model, it is more accurate to view these as parallel pathways—two configurations that serve similar performance ends but through different maintenance and refurbishment logics.

For operators and technicians, the practical upshot is clear. Confirming whether a particular MX engine uses sleeves or a parent bore must come from the engine’s service documentation for the exact model year and block designation in question. The maintenance plan should reflect the chosen architecture: sleeve‑based designs favor targeted liner service and possibly quicker in‑frame rebuilds, while parent bore blocks emphasize block integrity, disciplined honing, and, when necessary, block refurbishment or replacement. The best approach is to treat cylinder design as a foundational variable in lifecycle planning, not a fixed attribute that can be assumed across a fleet. In this way, maintenance economics, downtime, and reliability can be aligned with the actual engineering choice that governs a given engine at a given time.

External resources aside, the broader conversation about PACCAR cylinder design remains a vivid reminder that modern diesel engines are built not only to survive the pressures of the combustion chamber but to survive the logistics of keeping thousands of mountains of metal and precision surfaces moving every day. The science of cylinder walls—whether they are honored as a robust, monolithic bore or celebrated as the replaceable heart of a liner system—speaks to a fundamental engineering truth: durability, heat management, and serviceability must coexist in a way that keeps trucks on the road and fleets profitable. The MX series, with its varied design choices, embodies this balancing act. There is no one universal template; there are design families created to meet different priorities, and the best choice for a given fleet depends on the operational profile, maintenance philosophy, and the willingness to invest in the tooling and know‑how that keeps an engine alive when the miles pile up.

External resource: https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/DAF-PACCAR-MX-13-M-11-Engine-for-Truck_1601295784254.html

Sleeves, Blocks, and the Durability Equation: How PACCAR MX Engines Balance Overhaul, Efficiency, and Maintenance

The question of whether PACCAR diesel engines wear sleeves inside their cylinders opens a window into a broader engineering choice that shapes maintenance philosophy as surely as it affects performance. In the heavy-truck world, cylinder design is not a sterile technical footnote; it determines how fleets plan overhauls, how repair shops stock parts, and how long an engine can stay productive between major services. At the heart of this discussion lies a simple contrast: sleeved cylinders, with replaceable liners, versus solid, parent-bore cylinder walls that are machined directly into the block. The MX family from PACCAR—the engines that power many long-haul and vocational trucks—has become a focal point for this debate. While some sources paint the MX-11 and MX-13 as engines built on non-sleeved, parent-bore blocks, the practical maintenance narrative that accompanies these designs reveals a more nuanced picture. It is this nuance that carries through to how fleets approach reliability, downtime, and total cost of ownership when PACCAR power is under the hood.

To frame the discussion, it helps to unpack what a sleeved cylinder actually is and why it matters in heavy-duty service. Cylinder liners, or sleeves, are replaceable inserts that sit inside the engine block. In wet-sleeve designs, the liner sits in direct contact with engine coolant, which facilitates heat transfer and can simplify maintenance in the field. Dry sleeves, by contrast, are pressed into the block and do not contact coolant, offering different thermal and wear characteristics. In practice, sleeved designs generally enable in-frame repairs that avoid the need to fully remachine a block. Mechanics can pull a worn liner, install a fresh one, and resume service with minimal disruption. The choice to use sleeves is therefore not merely about wear resistance; it is about serviceability, downtime, and the economics of maintenance in high-mileage applications.

PACCAR’s MX engines, renowned for their torque, durability, and efficiency in heavy-duty trucking, are widely discussed in industry literature for their non-sleeved, parent-bore architecture. In a traditional reading, the MX-11 and MX-13 are described as blocks whose cylinder walls are integral to the cast-iron block, machined to precise dimensions rather than relying on removable liners. This design brings advantages: a stiffer block that can improve head gasket sealing under high cylinder pressures, a lighter and more compact package, and a streamlined manufacturing flow that can lower initial costs. The result is a package well-suited to modern emissions regimes, where precise combustion, robust thermal management, and durable sealing are as critical as raw power. Yet the story does not end with the block casting alone. The maintenance and repair ecosystem surrounding PACCAR engines reveals a persistent need for liners in certain scenarios.

The practical maintenance narrative that accompanies MX engines shows that, even if the cylinders are not sleeved from the factory, sleeves still appear in the lifecycle of an engine. When cylinder wear or scoring occurs beyond specification, the choices are not limited to a new block. In many repair scenarios, the approach involves either boring the worn bore to an oversize and fitting oversized pistons, or installing a repair sleeve, sometimes described in the trade as a maintenance sleeve, to restore a smooth, cylindrical surface. This repair path requires specialized equipment, clearances, and expertise, and it underscores a truth for operators: the presence or absence of factory sleeves does not permanently seal the door on liner-based repair strategies. Rather, it defines the initial maintenance posture and the strategic options available when wear accumulates over thousands of hours of operation.

The literature supporting this nuanced view emphasizes that genuine PACCAR cylinder liners exist for repair contexts, and that these parts are intended to be compatible with the engine’s original design tolerances. In some cases, fleets and repair facilities can source specific liner parts to recondition a worn bore while preserving the overall architecture of the MX block. The availability of liners such as those associated with PACCAR, identified in maintenance catalogs and cross-reference listings, signals a defined repair ecosystem that recognizes the realities of wear, heat, and the demanding service life of heavy-duty engines. It is in this context that the maintenance conversation shifts from “Is there a sleeve?” to “What repair path is most economical and fastest without compromising reliability?”

From a durability standpoint, PACCAR’s parent-bore approach benefits from the material science and manufacturing precision that underpins modern diesel engines. The MX family uses high-strength cast iron alloys and optimized surface treatments to resist wear, scuffing, and high-temperature distortion. The combination of tight manufacturing tolerances, advanced honing techniques, and careful thermal loading modeling during design helps maintain oil film retention and piston ring sealing across the operating envelope. These design choices support the engine’s ability to sustain high-output performance while meeting stringent EPA emissions standards. In practice, this means fewer surprises at the upper end of the torque curve and more predictable life for critical components like the piston rings and cylinder walls, even as the engines operate in challenging temperatures and pressures.

Nevertheless, the absence of readily removable sleeves can shape the economics of a rebuild. In-frame overhauls for non-sleeved engines tend to be more technically involved than those for engines with easily extractable liners. When cylinder wear exceeds limits in MX engines, mechanics must decide whether to bore to an oversized size and install corresponding pistons and rings, or to adopt a repair sleeve solution that reestablishes the original bore diameter within the block. Each path carries its own set of equipment needs, downtime, and precision requirements. The choice can hinge on the engine’s current bore condition, the availability of specialized tooling, and the preferred repair philosophy of the shop or fleet. The outcome is a maintenance profile that leans heavily on skilled technicians, precise measurement, and careful decision-making about the engine’s future reliability and performance.

The maintenance reality is also tied to the fleet’s supply chain and parts strategy. Operators who run PACCAR MX power have learned to anticipate the potential for bore wear and the subsequent need for repaired cylinders. The presence of genuine cylinder liners in the supply ecosystem—alongside the non-sleeved factory precision—adds a dimension of flexibility to maintenance programs. For example, genuine PACCAR liner parts have known fit and material compatibility with the engine’s original design, helping ensure that a repair liner results in consistent oil film retention, good piston ring sealing, and predictable wear characteristics in the next thousands of hours of operation. The trade-off, of course, is that repairing a worn bore with a liner is a different process than swapping in a brand-new, sleeved block. It requires careful alignment, honing, and lubrication planning to ensure that the repair reproduces the engine’s intended geometry and thermal response.

In terms of how this translates to the day-to-day reality of fleets, the MX engine’s design tends to favor overall block stiffness and cleaner coolant flow. Reduced coolant cavity complexity in non-sleeved designs can aid in optimizing coolant distribution, reducing cavitation risks, and sustaining stable temperatures under high-load operation. Those gains support durable combustion and long-term reliability, which are central to the value proposition of PACCAR engines in high-mileage applications. Yet the trade-off is that in-frame repairs, when necessary, demand more careful machining and sometimes a broader set of repair options than a typical sleeved engine. Fleets must weigh the benefits of stiffness and weight savings against the potential downtime and specialized repair steps required if bore wear becomes a limiting factor. The decision matrix becomes a matter of long-term planning: how many engines will operate with minimal downtime, how quickly can worn cylinders be repaired, and what is the total cost of ownership when considering block replacement as a last resort.

A final note on the repair culture surrounding PACCAR engines helps illuminate why the sleeves question remains a live topic. The maintenance literature often points to the importance of part provenance and fit, cautioning that aftermarket sleeves or non-genuine replacements may compromise ring seal, oil control, or heat transfer if the dimensions or coatings do not match the engine’s original design intent. The availability of genuine liners and the proper, factory-referenced installation procedures become crucial in achieving the expected service life after a bore repair. This perspective aligns with a broader industry caution: when you choose to repair with sleeves or to replace a block, you are selecting a pathway that can shape the engine’s reliability profile for the next cycle of service. The MX’s parent-bore architecture remains a strategic choice by PACCAR, one that emphasizes structural rigidity and thermal efficiency but also invites careful planning for overhauls when wear reaches the edge of the specified limits. For readers who want a primer on sleeves themselves, see What are engine sleeves? The linked resource helps anchor the discussion in a broader, engine-family context and clarifies the spectrum from wet to dry sleeves and their respective trade-offs.

In summary, do PACCAR diesel engines have sleeved cylinders? The clear answer is nuanced. The MX series is designed with a parent-bore cylinder wall, not a factory-installed wet sleeve. This design delivers stiffness, heat management, and a lightweight block that benefits emissions and performance. Yet the maintenance landscape does not disappear sleeves entirely. Repair sleeves and repair liners exist as viable options when bore wear demands intervention, and genuine PACCAR liner parts illustrate how a non-sleeved block can be restored without a full block replacement. This integrated view—block rigidity and efficiency on the one hand, repair flexibility on the other—frames a practical reality for operators: a design that minimizes downtime through robust engineering, while still offering a repair path when wear inevitably tests the engine’s life in the field. The chapter of maintenance is therefore not a simple yes-or-no on sleeves, but a narrative of design intent meeting serviceability in the crucible of heavy-duty operation.

Internal link reference: What are engine sleeves? for a primer on the sleeve concept and how it differs from factory sleeves and repair liners. https://itw-autosleeve.com/blog/what-are-engine-sleeves/

External resource: https://www.ebay.com/itm/Genuine-PACCAR-1974294-Diesel-Engine-Cylinder-Liner-Sleeve/363798022586

Sleeves, Strength, and the Emissions Equation: The Non-Sleeved Cylinder Approach in Paccar MX Engines

The question of whether Paccar diesel engines have sleeved cylinders is more than a hardware curiosity. It sits at the center of how modern heavy‑duty powertrains balance durability, serviceability, emissions compliance, and overall lifecycle cost. In the MX family, including the MX-11 and MX-13, the answer is clear: these engines do not rely on traditional wet sleeves. Instead, they employ a parent bore block design where the cylinder walls are an integral part of the cast iron block, precisely machined to tight tolerances. This choice reshapes how heat is managed, how wear is addressed, and how fleets plan maintenance over the life of a truck. It also reframes the conversation about engine overhaul, in-frame rebuilds, and the economics of uptime that matter most to fleets running long-haul and heavy-haul duties. To appreciate the implications, it helps to start with what sleeved versus non-sleeved designs actually do, and then to trace how the MX-13’s architecture translates into performance and emissions outcomes in real-world operation.

Sleeved cylinders—both wet and dry variants—are a familiar tool in the heavy‑duty toolbox. Wet sleeves sit inside the coolant jacket, giving an easily replaceable, heat‑conductive surface that can be renewed without resurfacing the entire block. Dry sleeves, in turn, are fixed inserts that do not contact coolant and serve mainly to restore bore dimensions when wear or damage occurs. In many fleets, sleeves have been championed for their rebuildability; you can recondition a worn cylinder by replacing the liner and restoring proper piston rings and seals, often without replacing the entire engine block. This rebuild pathway translates to a lower initial block cost and, crucially, a serviceability advantage when cylinder wear accumulates.

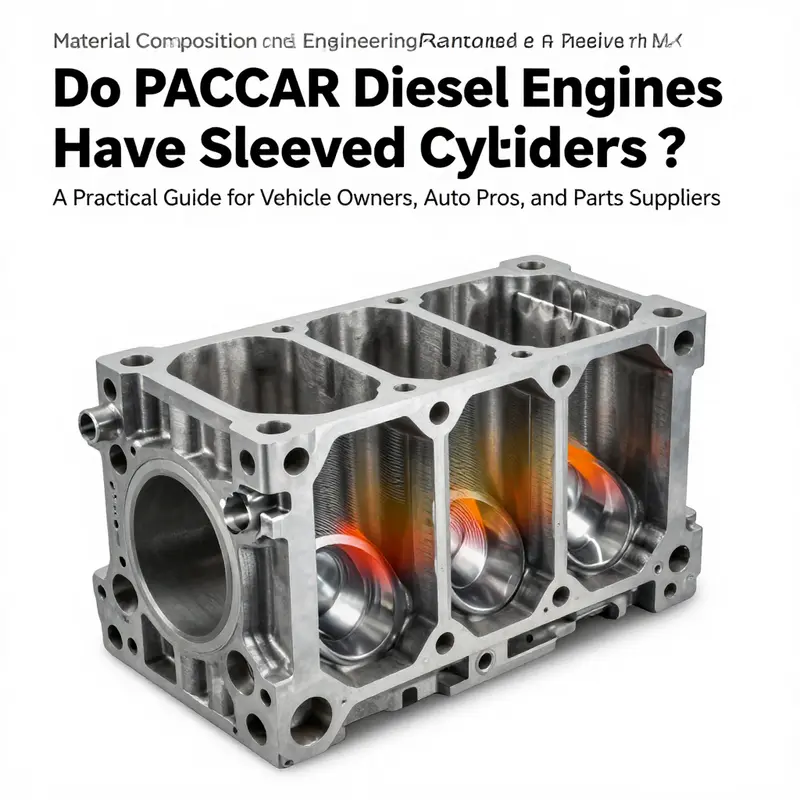

Paccar’s MX series takes a different route. The MX‑13, a 12.9‑liter inline‑six, and its sibling engines emphasize block rigidity, precise thermal management, and a design philosophy that aims to meet stringent emissions standards through structural and metallurgical excellence. By adopting a parent bore design, the walls of the cylinders are cast as part of the block itself, then honed to exact diameters. The absence of removable sleeves reduces cooling cavities and, in theory, lightens the engine’s mass while tightening the interface between the piston rings and the bore. Those shifts ripple through the engine’s heat cycle and its capacity to seal under high cylinder pressures as modern engines push toward higher outputs to meet EPA Tier 4 final/Euro VI requirements. A stiffer block can improve head gasket sealing when the engine operates under the elevated pressure swings that come with advanced emissions control strategies. Fewer, simpler coolant passages in the immediate bore area can streamline flow and reduce regions prone to localized boiling or cavitation, which are conditions that degrade heat transfer and accelerate wear.

But the non-sleeved approach is not a universal key that unlocks effortless maintenance. When cylinder wear becomes outsized—whether from siting, lubrication, or thermal cycling—the options within a parent bore block are different from those in a wet-sleeve engine. In a sleeved design, you might swap a liner, hone the sleeve, and reseal the piston rings with minimal block work. In a parent bore MX engine, wear beyond specification often means reboring the bore to an oversized diameter and installing a repair sleeve, or—less commonly but sometimes necessary—replacing the block. Each path has tradeoffs: the repair sleeve route can demand specialized tooling and precise interference fits; a full block replacement is costly and incurs more downtime. For fleets that prize uptime, those tradeoffs shift maintenance planning from the shop floor to a broader logistics and parts strategy. The MX design aims to minimize downtime through robust cylinder wall metallurgy, refined surface treatments, and process control that preserves oil film and ring seal integrity across many cycles of heavy loading, but it cannot pretend the wear path is identical to a sleeve‑based engine.

From a materials science perspective, the MX’s non-sleeved cylinders rely on high‑strength cast iron alloys and carefully engineered surface finishes. The cylinder walls receive optimized treatments to resist scuffing, wear, and high‑temperature distortion. Tight manufacturing tolerances and advanced honing techniques are employed to ensure that the oil film remains intact, providing proper lubrication for piston rings while maintaining ring seal under pressure. The emphasis on surface engineering, combined with a precise thermal model during design, helps offset some of the perceived drawbacks of a fixed bore. The result is a cylinder block that can withstand the thermal and mechanical demands of modern diesel operation without the flexibility of line‑replacing sleeves. Practically, that means the engine is resilient to the everyday stresses of heavy‑duty work, but the tradeoff appears in the maintenance mindset: you plan more for precision bore work than for sleeve replacement.

Thermal management is a central pillar of the non‑sleeved MX strategy. In high‑output diesel applications, cylinder pressures climb as exhaust aftertreatment systems drive more aggressive combustion. The parent bore design contributes to block stiffness, which, in turn, supports tighter head gasket sealing. With emissions equipment imposing additional thermal loads and with exhaust gas recirculation systems shifting the burn characteristics, the engine must manage heat with a high degree of reliability. Fewer coolant cavities in the vicinity of the bores can simplify coolant routing and reduce the risk of hot spots—areas where local boiling could undermine lubricant film integrity. In practice, this translates into more predictable thermal behavior over the engine’s life and fewer surprises under high‑duty operation. Yet, if a bore is reground and a repair sleeve is needed, the heat transfer paths can become more complex again, requiring meticulous machining and a disciplined approach to coolant flow optimization during the rebuild.

The maintenance implication grows clearer when one considers the lifecycle calculus fleets perform every year. With sleeved engines, the path to overhaul often centers on replacing liners and reestablishing proper clearances through standard machinist routines. With a parent bore MX engine, the same goal—restoring cylinder dimensions and sealing integrity—can require bore oversizing and the installation of a repair sleeve, or sometimes block replacement. Downtime will reflect this shift, along with the need for specialized tools and skilled technicians who can verify bore geometry, verify piston ring lands, and reestablish oil film retention with the requisite surface finishes. The economics of this non‑sleeved approach hinge on several variables: the severity of wear, the cost of replacement blocks or repair sleeves, the availability of skilled labor, and the duration of downtime that fleet operators are willing to tolerate between cycles of maintenance and repair.

When reading about the MX‑13 and similar engines, it is easy to conflate durability with a lack of serviceability. In truth, the durability of a parent bore design rests on robust metallurgy, reliable honing, and the engine’s overall thermal and mechanical design. The parent bore approach does not inherently condemn the engine to shorter life if wear goes unchecked. Rather, it defines a different repair language: one that emphasizes precision restoration of bore geometry, controlled material removal through honing and reboring, and, when necessary, the insertion of sleeves produced to exact specifications. The language of maintenance, then, becomes more about controlled, high‑precision machining than about quick sleeve swaps. This has implications for maintenance planning: technicians must be equipped to manage bore oversizing and to select compatible pistons and rings, ensuring the overall piston–bore clearance remains within engineered tolerances. Fleet managers, too, must adapt their spares and scheduling to accommodate the longer or more complex overhauls that a non‑sleeved design may require at times, even as the engine delivers steady performance and reliable emissions compliance when operated within its design envelope.

For engineers and operators, one practical takeaway is the way bore integrity is safeguarded from the outset. The MX family incorporates rigorous design practices, including simulated thermal loading, precise honing protocols, and tolerances that are intended to keep oil film and piston ring sealing dependable across a broad operating window. The goal is to minimize the probability that a bore will wear so aggressively that a standard repair sleeve becomes necessary. The tradeoff is not only about whether a sleeve exists, but whether the design can maintain performance and emissions targets as wear accumulates. In recent years, as emissions standards have grown more stringent and engine cycles have grown longer between major overhauls, the benefits of a stiff, well‑calibrated block have become more pronounced. This is not a novelty; it is a strategic choice aligned with a broader shift in heavy‑duty engine design that prizes structural rigidity and thermal efficiency as pathways to meet modern requirements while reducing overall lifecycle cost for operators.

From a reader’s perspective, a useful touchstone is to consider how a discussion of sleeves becomes a discussion about reliability, uptime, and total cost of ownership. A technical decision about whether to sleeve a cylinder is not isolated from system integration: piston rings, oil films, coolant flow, turbochargers, and aftertreatment all interact in a tightly coupled regime. In the MX design, the fixed bore places a premium on accurate assembly and surface finishing. When done correctly, the engine can sustain long hours of service with strong seal integrity and robust heat management. When not, the consequences manifest in wear patterns that demand careful machining and, eventually, a decision about whether to rebuild or replace the block. The outcome depends on the quality of manufacturing, the consistency of maintenance practices, and the operating profile of the fleet.

For readers who want to explore a broader question alongside this chapter—whether all engines have cylinder sleeves—there is a concise explainer that discusses the sleeve concept across engine families. Do all engines have cylinder sleeves? offers a compact overview that helps place the Paccar MX approach in a wider context and aids comparisons across manufacturers. Do all engines have cylinder sleeves?.

In closing, the MX‑13 and related MX engines epitomize a deliberate design decision: to optimize for block stiffness, refined thermal management, and emission compliance through a parent bore architecture. This choice reshapes maintenance workflows, challenging repair shops to adopt more precise bore restoration strategies and prompting fleets to recalibrate their expectations about in‑frame rebuilds. It is not a rejection of sleeves as a concept; it is a prioritization of structural integrity and thermal efficiency as the backbone of modern heavy‑duty diesel performance. As emissions regimes continue to tighten and fuel economy becomes an even more salient metric of success, the non‑sleeved, parent bore pathway will likely remain a defining feature of how these engines deliver uptime, reliability, and the power to sustain demanding operations on the road and beyond.

External reference: For additional context on cylinder liner components and sleeve considerations in modern engines, see a dedicated resources page discussing sleeves and their costs: https://www.ebay.com/itm/1859279-Genuine-PACCAR-Diesel-Engine-Cylinder-Liner-Sleeve-for-MX-Series/.

Sleeved Cylinders, Steady Miles: The Engineering and Economics of PACCAR MX Sleeves in Heavy-Duty Fleets

The core question—do Paccar diesel engines have sleeved cylinders?—reads like a technical footnote in a broader discussion about heavy-duty reliability and fleet economics. Yet the answer shapes maintenance strategies, downtime planning, and the long-term cost of ownership for the trucks that power long-haul corridors, regional deliveries, and demanding vocational work. In the PACCAR MX family, which underpins popular long-haul platforms in the heavy-duty segment, cylinder design is not an afterthought but a central lever that influences heat management, wear patterns, and serviceability. The sleeves-versus-parent-bore debate often centers on what happens when cylinder walls wear, how repairs are performed, and how quickly a fleet can get back on the road after a hot-swap of a worn wear surface. The story of the MX engines, however, is a story of sleeves that help maintain consistent bore geometry, preserve piston-ring sealing, and support predictable maintenance cycles that fleet managers prize as much as horsepower or torque curves.

Cylinder sleeves act as replaceable wear surfaces inside the engine block. In PACCAR MX engines, these sleeves are designed to form a precise bore for the pistons while serving as a separate, replaceable element when wear becomes evident. The materials chosen for sleeves in heavy-duty diesels are typically high-grade cast iron or other durable alloys, coupled with surface treatments that resist scuffing, micro-welding, and high-temperature distortion. What matters most for fleet operators is not the raw material alone but the functional role these sleeves play: they provide a reserve layer that can be renewed without ripping out the entire cylinder block. This is particularly relevant in high-usage fleets where engines accumulate miles quickly and the burden of a full block replacement would translate into multi-day downtime and substantial labor costs.

The MX series’ sleeves are integrated into a block architecture that prioritizes reliable heat transfer and consistent bore geometry. In practical terms, a worn bore can be addressed by replacing the sleeve rather than milling a new, oversized hole in the block. The resulting repair surface is designed to be compatible with the engine’s piston rings, oil film retention, and the seal interfaces that keep compression and combustion byproducts in their respective domains. This approach complements the engine’s overall thermal management strategy, where careful alignment of coolant flow, combustion chamber geometry, and oil film behavior works in concert to minimize hot spots, local boiling, and cavitation risks. In fleets, this translates into more predictable performance across heat cycles, especially as emissions standards push engines toward higher mean effective pressures without proportionally increasing thermal loads.

From a maintenance economics standpoint, the presence of sleeves offers tangible benefits. When cylinder wear progresses to a threshold that reduces compression or increases oil consumption, technicians can replace just the sleeve—a procedure that is generally faster and less invasive than reconditioning or rebuilding the entire block. The ability to perform sleeve replacements in a controlled, in-situ manner reduces downtime and capital expenditure, a factor fleets weigh heavily when scheduling maintenance windows around delivery deadlines and service commitments. This modular approach underpins a maintenance philosophy that favors component-level overhauls, which many fleet managers associate with greater uptime and more predictable maintenance budgets. The economics here are not merely about the cost of a sleeve versus a block; they are about the labor topology of repairs and the time-to-ship that a fleet can reclaim after a service event.

To understand the maintenance workflow in practice, consider the lifecycle of an MX engine in a high-mileage application. When the cylinder bore shows wear that still leaves a serviceable surface, a sleeve replacement can restore the original bore diameter and surface finish, recapturing seal integrity and compression performance. If wear continues beyond what a sleeve can accommodate—perhaps in the most arduous operating conditions or with extreme duty cycles—technicians may re-bore to an oversize dimension and install a repair sleeve or, in more extreme cases, escalate to block replacement. This sequence—sleeve replacement, possible re-bore with oversize components, and ultimate block refurbishment if needed—frames a predictable maintenance ladder. It’s a ladder fleets can climb because the sleeve is a modular wear surface, a feature that aligns well with the modern maintenance philosophy of planned downtime, rather than reactive overhauls after failing cylinders.

The durability story is not simply about wear surfaces and easy fixes. It also hinges on how sleeves interact with the engine’s combustion dynamics and thermal environment. The MX engines operate at high output levels, where pressures, temperatures, and fuel energy demand robust metallurgy and precise tolerances. The sleeves, paired with tight machining tolerances and refined honing techniques, help ensure consistent oil film retention around the piston rings and steady sealing on the cylinder walls. The result is stable compression, efficient combustion, and reduced variability in fuel economy across a fleet that may include a mix of long-haul, regional, and vocational duties. In other words, sleeves support the engine’s overall reliability by maintaining bore integrity under the duress of modern emissions-compliant operation, where higher peak pressures and tighter tolerances can otherwise magnify wear patterns if the wear surface were not readily renew-able.

The fleet-management perspective extends beyond the mechanical virtues of sleeves. Fleet operators weigh the entire ecosystem of spare parts, service protocols, and the availability of qualified technicians. A credible maintenance plan for MX-powered fleets prioritizes genuine or properly engineered sleeves, compatible pistons, rings, and associated hardware. The modular nature of sleeve design makes it sensible to stock a balanced inventory of wear parts that can be swapped in during scheduled maintenance or unplanned downtime. Operators often plan around the expected service intervals for sleeves, knowing that this part, while durable, has a finite life under extreme duty cycles. The economics of this planning favor predictable, scheduled downtime over extended, unplanned outages, and that predictability is precisely what sleeves are meant to deliver in a fleet setting.

There is also a broader conversation about how sleeve design interacts with the evolving emissions landscape and the push toward weight reduction and structural rigidity in modern engine blocks. While some engine families have pursued parent-bore architectures to maximize block stiffness and reduce coolant-circuit complexity, the MX series has embraced sleeves to support durable, serviceable wear surfaces without sacrificing the benefits of precise bore finishing and heat management. The design choice—sleeves with robust wear characteristics—reinforces a practical principle in fleet operation: you win not just with horsepower, but with a predictable, repeatable maintenance pattern that minimizes the time engines spend out of service. In this sense, sleeves are not merely a technical feature; they are a strategic asset that helps convert high-capacity engines into reliable toolsets for complex logistics networks.

Readers often encounter broader questions about cylinder sleeves in the industry. A common inquiry is whether all engines use sleeves, and if sleeves are universally necessary for longevity. The nuanced answer is that sleeves are a design choice, optimized for a given set of performance, durability, and serviceability goals. In the PACCAR MX lineage, sleeves are the chosen wear surface, aligned with the brand’s emphasis on durability and repairability within a governed maintenance framework. This alignment matters for fleet managers who are balancing upfront engine costs, depreciation timelines, and the cost of downtime during planned and unplanned repairs. The logistical calculus favors sleeves when the maintenance strategy relies on replacing a wear surface rather than the more disruptive option of refurbishing or replacing a block entirely.

To help frame these points for readers navigating maintenance decisions, it is useful to connect the discussion to the broader literature on engine sleeves. For a concise overview that situates sleeves within common diesel-engine practice, readers may explore discussions like the general concept of sleeves and their role in wear surface maintenance. Do all engines have cylinder sleeves? is a question that recurs in shop conversations and parts catalogs, and the answer varies with design philosophy and application. The MX engine’s approach—sleeved cylinders with precise machining, high-integrity materials, and controlled thermal loading—illustrates a practical implementation where sleeves support both performance and fleet uptime. This is precisely the kind of engineering trade-off that fleet operators weigh when selecting powertrains for a given duty cycle, ambient conditions, and maintenance ecosystem.

For practitioners seeking further alignment with maintenance literature, the MX approach is consistent with the broader principle that a well-designed sleeve system can enable predictable service intervals and a modular approach to repairs. It underscores a key point for managers: when a bore wears, the repair path is not necessarily a block replacement; it can be a sleeve replacement that reestablishes the intended bore geometry and performance envelope. In the end, the sleeve is not just a wear component; it is a strategic interface between the engine’s core dynamics and the fleet’s demand for reliability, uptime, and efficient lifecycle economics.

As fleets plan for the future, the sleeve-centered design of PACCAR MX engines suggests a maintenance philosophy anchored in component-level renewal and controlled obsolescence. It supports the expectation that engines can sustain long lifespans with periodic, targeted interventions rather than wholesale rebuilds. In this sense, sleeves contribute to a more predictable, more manageable upgrade path for older platforms and newer models alike, aligning maintenance costs with actual performance needs and actual wear, rather than with an uncertain trajectory of block integrity over the engine’s life.

External resource: https://www.dieselnet.com/tech/diesel_engines/cylinders.php

Internal link reference: Do all engines have cylinder sleeves

Final thoughts

The MX-11 and MX-13 engines from PACCAR adopt a sleeveless, parent bore cylinder design. This choice strengthens block stiffness, simplifies certain heat management pathways, and supports robust emissions performance, while changing how shops approach in-frame rebuilds and cylinder wear. For motorcycle and auto owners, understanding this design helps set expectations for service intervals and repair strategies. Auto repair shops and parts distributors benefit from recognizing that, unlike traditional wet-sleeved diesel blocks, these engines may require bore machining, repair sleeves, or block replacement when cylinder wear progresses beyond specification. Fleet managers should factor in these maintenance realities into total cost of ownership, balancing reduced upfront complexity with potentially longer downtime and specialized machining needs. Across the five chapters, the central thread remains: sleeveless cylinders in PACCAR MX engines are a deliberate design trade-off, optimized for stiffness, heat flow, and emissions, with clear implications for maintenance workflows and lifecycle economics. The key takeaway is practical clarity—engine design decisions today influence the ease or complexity of repairs tomorrow, and informed decision-making hinges on acknowledging the sleeveless reality of PACCAR’s MX engines.