Cylinder sleeves, or cylinder liners, have long been a feature in many engines, providing wear resistance, bore integrity, and reliable heat management. Yet not every engine relies on sleeves. Modern designs—especially in lightweight aluminum blocks—often form the combustion bore directly in the block (sleeveless) or use an integrated sleeve cast into the block. This shift affects maintenance, replacement-part availability, and service techniques. A broad view across motorcycles, passenger cars, and the auto-parts supply chain reveals a nuanced landscape: sleeves remain common in many generations and regional practices, but sleeveless architectures are growing where weight, cooling efficiency, and manufacturing costs favor them. The four sections below tie these threads together. First, a historical look at prevalence and evolution; second, a comparison of sleeve-based versus sleeveless architectures in materials, manufacturing, and performance; third, wear, heat transfer, and reliability considerations across engine types; and fourth, the economic, regional, and environmental factors shaping adoption and future trends. Readers include motorcycle owners, auto owners, distributors and wholesalers, and repair shops seeking practical insight into how sleeve design affects parts compatibility, service procedures, and long-term ownership logistics.

Do All Engines Have Cylinder Sleeves? A Century-Long Tale of Bores, Blocks, and the Coatings That Made Modern Engines Possible

The question may sound simple, but it opens a window into how engineers balance heat, wear, weight, and maintainability. Cylinder bores are where the pistons travel, and every scratch, glaze, or unevenness in that surface can ripple through an engine’s efficiency and longevity. For much of automotive and industrial history, the sleeve—an insert that defines the bore—was the practical answer to wear, repair, and heat management. Yet not every engine uses a sleeve, and in recent decades a steady shift has occurred toward sleeveless blocks and advanced bore coatings. The story is not a straight line but a tapestry of tradeoffs, material science, and manufacturing capability that reveals why some engines still rely on a liner while others boast a bore formed directly in the block or integrated into an aluminum skeleton. To grasp this, we start with the basic roles of sleeves and then trace the design path through eras, scales, and applications. A sleeve, whether wet or dry, serves as a dedicated surface for the piston rings and as a shield for the block itself. In a wet sleeve, the liner sits in direct contact with coolant on its outer surface, which aids heat removal and helps control bore temperature during combustion. In a dry sleeve arrangement, the liner is more a matter of interference fit within the block, contributing to bore geometry and wear resistance while sharing the cooling and sealing responsibilities with the block itself. This distinction matters, because it shapes everything from thermal behavior to serviceability. It is tempting to imagine sleeves as a universal solution, but the engine families of the 20th and 21st centuries tell a more nuanced tale. Early engines often bore directly into the cast material of the block or into cast iron linings when added durability was needed. The bore surface in those early machines benefited from robust casting techniques and the relatively forgiving properties of cast iron or steel. As power demands intensified and engines grew larger, the need for wear resistance, repair ease, and maintenance access prompted a shift toward cylinder liners in many heavy-duty and marine diesel platforms. Wet sleeves, in particular, gained prominence in engines where heat and fuel quality created demanding thermal cycles and where the ease of reconditioning worn bores through liner replacement offered a practical maintenance pathway. The dry-sleeve approach, more common in automotive light-truck and passenger-car engines, brought advantages of easier bore control, simpler overhaul paths, and the opportunity to tailor the bore surface without pulling a liner. The surface that actually bears the piston rings, however, is where modern engineering has pushed the envelope most aggressively. If we look at today’s engines, the picture is a blend. Some engines still rely on a traditional liner, especially in large-displacement, heavy-load applications where the liner’s replacement remains a straightforward, cost-effective service step. But in many automotives and performance-focused platforms, manufacturers have moved toward sleeveless blocks or integrated bore concepts, where the cylinder wall is formed directly in the block, often made of aluminum to gain weight and heat-management benefits. In these sleeveless designs, the bore may be ground into the block with a precision that requires advanced tooling and tight tolerances, or it may utilize a sophisticated coating on the bore surface to deliver wear resistance without a separate metal sleeve. The coatings landscape is a critical part of this evolution. Nickel-silicon carbide ceramics, known in industry discussions as Nikasil-like coatings, have been applied to aluminum bores to dramatically increase surface hardness and reduce wear, allowing engines to forgo traditional sleeves while keeping the lightness and thermal advantages of aluminum blocks. Plasma-spray coatings, too, have played a significant role by enabling tailored properties—friction reduction, improved thermal handling, and durability—directly on bore surfaces or liner surfaces when a conventional sleeve remains in place. The material choices continue to reflect a balancing act: cast iron sleeves provide durability and oil retention but add weight and thermal mass; aluminum blocks enable better heat transfer and lighter weight but demand surfaces with extreme wear resistance, often achieved by coatings or by incorporating durable steel sleeves in a lightweight cast or forged aluminum matrix. When we speak about monobloc or integral-block concepts, we touch the frontier where the line between “sleeve” and “bore” begins to blur. In sleeveless designs, the bore is essentially an integral feature of the block; the walls can be formed through precise casting or machining and then finished with coatings that emulate or surpass the performance of a traditional liner. This approach is particularly appealing in high-performance and weight-sensitive applications, where every gram matters and the engine dynamics demand rapid heat dissipation. The argument for integrated bores often hinges on heat transfer. Aluminum, with its high thermal conductivity, can shed heat more efficiently than iron, helping to manage peak combustion temperatures and reduce heat soak that can accelerate wear. Add a robust coating or a durable inserted surface, and the bore can resist the wear that would otherwise erode the surface in a sleeved design. Yet this path requires exacting manufacturing discipline. The bore must be uniform, the coating must adhere to consistent thickness, and the interfaces with cooling channels and lubrication must be leak-tight. The production realities of modern engines—high volume, tight tolerances, and the demand for reliable parts—mean that the choice between sleeves and sleeveless blocks is not a mere preference but a calculated decision tied to the engine’s duty cycle, weight targets, and service philosophy. In large engines and industrial applications, the sleeve remains a stalwart. Wet sleeves, sometimes paired with robust coolant circuits, offer a straightforward path to wear control in engines that operate under heavy pressures and high thermal loads. The ability to recondition a worn bore by replacing the sleeve, rather than rebuilding an entire block, remains a practical advantage in long-life, high-use settings. The trade-off, of course, is the added mass and the potential sealing considerations where the sleeve interfaces with coolant passages. In automotive engines, the narrative is different. The rise of aluminum blocks with bore coatings—sometimes paired with micro-textured or ceramic-like surfaces—has enabled a lighter engine footprint without compromising wear resistance. The bore surface in these designs is a high-precision canvas, and coatings provide the hard-wearing skin that protects against pitting, scoring, and adhesive wear across many cycles of ignition, detonation, and rapid thermal swings. The coatings themselves are a field of ongoing research and refinement. They are chosen for their ability to maintain low friction, support long bore life, and withstand thermal excursions that would otherwise degrade a plain metal surface. The coating’s adhesion to the substrate, its thermal expansion compatibility, and its resistance to coolant exposure all become critical to success. Engineers must also consider sealing and lubrication. In wet-sleeve designs, the liner is part of a sealed system that includes gaskets, o-rings, and careful coolant management to avoid leaks. In sleeveless and coated-bore designs, the sealing strategy shifts toward ensuring the bore’s finish, the coating’s integrity, and the block’s mating surfaces maintain compression without deforming under thermal load. These choices of seal and surface finish feed directly into maintenance practices. Worn bores in sleeveless engines can be refurbished by recoating or by specialized overhauls that restore the surface to spec. In more traditional sleeved designs, the repair may involve swapping the liner and/or reboring, depending upon the make and model and the engine’s service philosophy. The practical takeaway for designers and technicians is that sleeves are not a universal necessity. They were a dominant technology for many decades and remain essential in many heavy-duty, high-load, or legacy systems. Yet for other engines—where weight, heat transfer, and simplified maintenance are paramount—engine blocks can be built sleeveless or with integrated, bore-coated surfaces that deliver comparable wear resistance without the extra interface of a traditional liner. This evolution is not merely a trend but a reflection of how materials science, precision manufacturing, and performance demands push engine architecture toward increasingly integrated solutions. The broader implication is clear: the bore is not a fixed part but a frontier where materials, coatings, and geometric precision meet the engine’s mission. If you want to explore more about the fundamental concept behind engine sleeves and the modern alternatives, a concise primer on What are engine sleeves provides a compact overview, and for deeper, technically rigorous discussions, the technical literature and industry resources such as SAE International offer a wealth of research and case studies that illuminate how sleeveless and coated bore technologies are implemented in practice. For readers seeking further technical grounding, consult the SAE International resources: https://www.sae.org.

Sleeves, Sleeveless, and the Quiet Engineering Trade-Offs That Shape Modern Engines

Do all engines wear the same wall? The short answer is no. The longer answer is that engine designers choose cylinder walls—the heart of the combustion chamber—based on a balance of weight, heat, durability, repairability, and the realities of the manufacturing line. This choice bifurcates engines into sleeve-based systems, where a distinct cylinder liner sits inside the block, and sleeveless or integral designs, where the wall is machined directly into the block itself. Each architecture carries a distinct philosophy about how an engine should handle heat, wear, and service life, and each has an effect on performance, maintenance, and even the kinds of problems a mechanic might face years after the vehicle leaves the showroom. The question “do all engines have cylinder sleeves?” therefore dissolves into a discussion of materials, processes, and intended use, rather than a single yes-or-no verdict. In this chapter we walk through the logic behind sleeve-based and sleeveless configurations, tracing how their differences ripple through heat management, durability, repair strategies, and the design ambitions that modern engines chase.

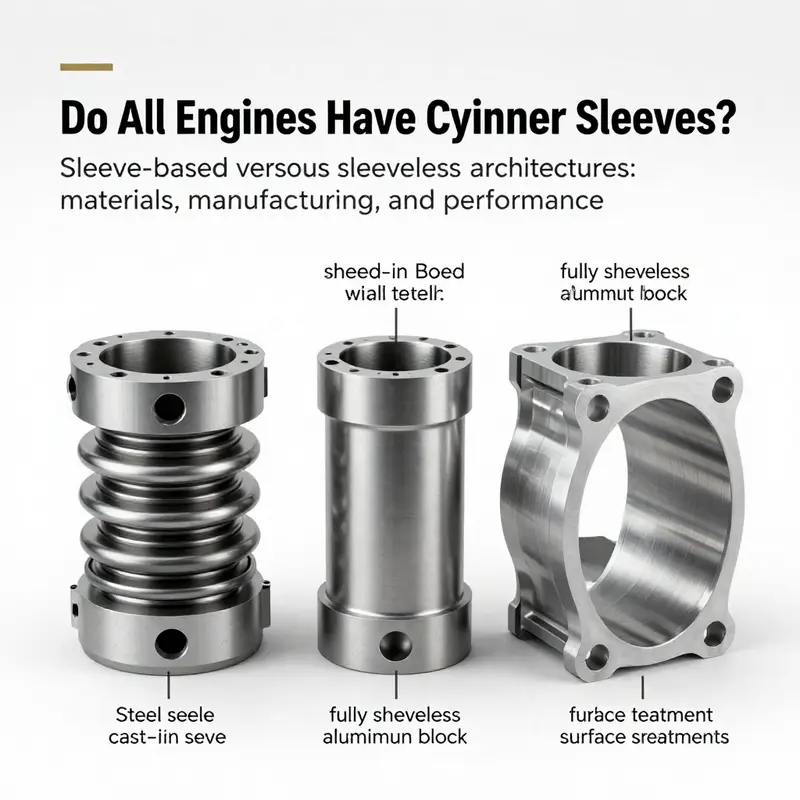

In a sleeve-based engine, the cylinder wall is a separate entity from the block. It can be a wet sleeve, directly cooled by engine coolant, or a dry sleeve, which sits inside the block but above the coolant boundary in a way that is less involved with the cooling system. Wet sleeves, when used, stand up to extreme heat and high combustion pressures because the liner itself is built from high-strength alloys designed to dissipate heat rapidly into the cooling circuit. The coolant is in contact with the liner, so heat transfer happens across a metal-to-fluid interface, helping to prevent localized hotspots. This approach is common in high-output diesel applications and other heavy-duty contexts where the engine endures sustained thermal loads and the risk of liner distortion or wear must be tightly controlled. The trade-off is a greater manufacturing and assembly complexity: liners must be precisely press-fitted or cast into the block, and the seal between liner and block must withstand thermal cycling and vibration without leaking. The result is a robust architecture that can be rebuilt by replacing the liner rather than the entire block, a repair path that appeals to fleets and heavy-duty operators seeking long service intervals and lower total cost of ownership.

Dry sleeves, by contrast, sit snugly inside the block without sharing the same level of coolant contact. They are easier to seal and can be suited to engines where coolant routing is optimized around a cast, integrated structure. The liner material—often cast iron or steel—is selected for wear resistance and dimensional stability when heated and cooled. The outer block provides the cooling and supports the liner, but the liner still bears the brunt of piston and ring wear. Because the sleeve is a mechanically distinct element, designers can tailor its surface finish and hardness to the specific demands of the engine. Yet even with dry sleeves, the non-sleeve area of the block remains a significant part of the heat path. The result is a design that balances wear resistance with a relatively direct fabrication route, still offering the ability to service the liner in some contexts without full engine replacement, but often at a higher complexity than a sleeveless block when it comes to reboring and re-sleeving.

If we track the reasons behind the sleeve-based approach, heat management and durability rise to the top. The sleeve gives the piston’s immediate surroundings a hardened, exchangeable surface that can be upgraded or replaced as the engine ages. For fleets that run engines for tens of thousands of hours, or for machines operating in harsh environments, sleeves provide a predictable, serviceable path. A core advantage is repairability: instead of scrapping an entire engine block when the cylinder walls wear out or crack, technicians can remove and replace a worn liner. This can translate into lower repair costs and shorter downtimes in contexts where reliability is the currency of business. However, the manufacturing precision required to fit a liner into a block introduces its own costs: the connection between liner and block must be engineered with exact tolerances to avoid leaks, misalignment, or differential thermal expansion that could lead to bore distortions or head gasket failures.

Sleeveless or integral designs represent a different engineering philosophy—one that leans into weight reduction, thermal efficiency, and the elimination of an interface. In modern engines, especially those targeting high specific output and fuel efficiency, aluminum blocks dominate the sleeveless landscape. The absence of a separate liner reduces mass and minimizes the number of boundaries across which heat must travel, which can improve thermal conductivity and enable more aggressive timing and tuning without overpowering the cooling system. To ensure wear resistance in the absence of a steel-lined barrier, engineers rely on advanced surface technologies. Coatings such as molybdenum disilicide, plasma-sprayed layers, or even advanced manufacturing techniques like direct metal laser sintering contribute to a hard, wear-resistant cylinder wall. These coatings must be uniform, adherent, and stable across a broad temperature range and repeated thermal cycles. The advantages are clear: fewer parts, lighter weight, fewer failure modes at the liner interface, and the potential for tighter tolerances in the cylinder bore that enable more efficient sealing with modern piston rings and sealing technologies. The trade-off, however, is that if the bore is damaged, repairing it becomes more challenging. A sleeveless bore can be overbored and reinforced with inserts, or the entire block may require refurbishment. The repair solution is less modular than simply replacing a liner, which can influence depreciation, maintenance planning, and the perceived reliability of the design in the eyes of buyers who value field serviceability.

The choice between sleeve-based and sleeveless architectures does not occur in a vacuum. It emerges from a broader calculus that includes material science, manufacturing realities, and the target application. For passenger cars that emphasize light weight and compact packaging, sleeveless designs often win out. The advantages of reduced weight and improved heat transfer sit well with modern turbocharged, high-efficiency engines that must manage heat with smaller, quicker-reacting cooling systems. For industrial or heavy-duty use—where engines are expected to endure extended cycles at elevated loads—the ability to replace a worn liner without discarding the entire engine block keeps operating costs predictable and downtime manageable. In such contexts, the complexity of a sleeved design can be more palatable than the burdens of an all-new block design, particularly when the block is cast as a high-strength alloy with precise bore tolerances. The decision is rarely about a single metric; it is about the alignment of architecture with duty cycle, maintenance philosophy, and the total cost of ownership over the engine’s life.

What does this mean for the everyday driver or the mechanic who encounters an aged engine? It means that the cylinder wall is not simply a stubborn obstacle to performance; it is a design choice with implications for heat management, wear characteristics, and repair strategies. If a technician learns that an engine uses a wet sleeve, the cooling system’s health becomes a central concern, because leakage or improper coolant flow can directly jeopardize liner integrity. If the engine is sleeveless, the focus shifts toward ensuring the bore’s coating remains intact and free of anomalies that could compromise seal longevity or ring seating. In either case, the maintenance approach is different from the days when a cast iron block and a uniform bore were the universal standard. The modern engineer’s toolbox—comprising coatings, surface finishes, and advanced materials—reflects a nuanced attempt to tune the wall of the combustion chamber to the engine’s intended mission.

As with many engineering decisions, there is no universal rule that can be applied to every engine across the spectrum of automotive and industrial powertrains. The answer to whether all engines have cylinder sleeves depends on recognizing the twin narratives of sleeved and sleeveless architectures. Each path has matured through decades of design evolution, material science breakthroughs, and the shifting demands of efficiency, emissions, and repairability. Where a sleeve-based design might offer unmatched durability and repair pathways for certain heavy-duty roles, sleeveless engines push the boundaries of light weight and thermal efficiency for small, densely packed powerplants. The landscape continues to evolve, driven by advances in materials—new alloys, coatings, and additive manufacturing techniques—that continually reshape what is feasible for cylinder walls. In this sense, the sleeve debate is less about a binary categorization and more about a spectrum of architectures optimized for different performance goals and lifecycle expectations.

For readers seeking a concise primer on the topic, a practical overview of engine sleeves can be found in resources that distill the material and manufacturing considerations into accessible terms: What are engine sleeves? This primer anchors the broader discussion of how sleeves fit into the architecture of modern engines and why some designs opt for a sleeve and others push further into sleeveless territory. What are engine sleeves? This kind of primer is useful when evaluating whether a particular engine is likely to respond well to certain maintenance strategies, or when considering how a future engine with a similar mission profile might be engineered.

In looking ahead, the chapter’s core insight remains: cylinder sleeves are not a universal feature of all engines. The most compelling engines are those that align their walls with their workloads, and the most resilient designs are those that anticipate the needs of repair, reuse, and upgrade. As the field advances, material innovations and new fabrication techniques will continue to blur the line between sleeve-based durability and sleeveless efficiency, enabling engines that simultaneously wear less, heat better, and last longer. For a deeper dive into the standards and technical context behind these ideas, reference to authoritative, externally hosted materials can be found in sources that discuss engine construction principles in more formal terms. For a broader technical foundation, see established engineering resources that illuminate the standards, testing, and performance data that underpin modern cylinder-wall design. SAE International remains a key repository for such framework discussions and is worth consulting for readers who want to connect the practical manufacturing choices discussed here with industry-wide norms and evolving guidelines.

Sleeves and Sleepless Bores: How Cylinder Design Shapes Wear, Heat, and Longevity Across Engine Types

The question, do all engines have cylinder sleeves, invites more than a yes or no answer. It invites a tour through the design logic that underpins modern engines, where every bore is a decision about weight, heat, wear, and the life cycle of the machine. In many ways, sleeves are not a universal feature but a targeted solution. They are a tool engineers deploy when the operating environment demands a robust, replaceable interface between moving parts and the block that houses them. Yet in other engines, the bore is cast or machined directly into the block, a sleeveless approach that leans on advanced materials and coatings to keep wear and heat in check. Reading the landscape of sleeved versus sleeveless designs reveals a spectrum of engineering trade offs that stretch from the laboratory to the showroom floor and into the field where engines live their hard lives.

To begin with, the sleeved family is anchored in a straightforward premise: the sleeve, typically a cylinder liner made from high strength steel or cast iron, sits inside the engine block and provides a dedicated, wear resistant surface for the piston and its rings. The sleeves can be dry or wet. Wet sleeves are bathed in coolant, offering excellent heat transfer and a direct path for thermal management when the engine is pushed hard or when turbocharging and high boost are in play. Dry sleeves, by contrast, rely on conduction through the block and its walls. They are simpler from a sealing standpoint and can be advantageous in certain light to medium load applications where the coolant flow is optimized around the liner area but the absolute cooling needs are more modest. Either way, sleeves add a modular dimension to engine maintenance. If a bore wears or corrodes, a sleeve can be replaced or refreshed without recasting the entire block. This is a tangible benefit for longevity and overhaul economics in engines that endure high thermal and mechanical loads over many years.

On the other side of the design ledger lies the sleeveless engine. Here the combustion chamber and the cylinder walls are formed directly in the block material, most commonly aluminum for lightweight performance or cast iron for robust higher load applications. When the wall is machined directly into the block, the bore surface is constrained by the block matrix, and wear protection becomes a function of surface engineering rather than a separate insert. To counter wear, manufacturers lean on hard coatings and surface treatments that harden the bore and reduce friction. Nikasil, a nickel silicon carbide coating, is one familiar example from the broader history of coated bores, though modern iterations often involve plasma sprayed layers or tailored aluminum silicon alloys designed to enhance hardness and reduce seizure risk. The practical effect is a lighter, simpler, and potentially less costly bore in production, with fewer parts and fewer potential leak paths around a liner. Yet the absence of a replaceable sleeve means failures in the bore surface can become more costly to repair, and reboring or bore widening might be necessary to restore sealing and oil control. The reliability equation thus shifts: sleeveless designs trade the easy refurbishment of sleeves for the need to rely on coating integrity and material performance over time.

Heat transfer is perhaps the most practical battlefield where these choices reveal their consequences. Wet sleeves furnish direct contact between coolant and the bore, enabling efficient heat removal during peak power output, aggressive driving cycles, or high thermal load scenarios. This makes wet sleeves particularly attractive in heavy duty or high output engines where temperature management is a primary constraint. Dry sleeves depend on conduction through the block walls and can be adequate when the coolant channel geometry is optimized and the thermal load is predictable and moderate. Sleeveless designs shift heat management to the block and the internal cooling passages. Aluminum blocks, with their low density and high thermal conductivity, can dramatically improve heat spread, provided the coolant flow is well engineered to avoid hot spots. The research literature consistently shows that well designed heat transfer through bore surfaces correlates with improved efficiency and reduced risk of pre ignition or warping under sustained loads. The caveat is that this advantage hinges on materials, coatings, and manufacturing tolerances that can push the cost and complexity of production higher.

The wear implications of these choices are equally nuanced. A sleeve, particularly when it is replaceable, acts as a sacrificial and serviceable wear surface. Over time, the ring lands and the piston skirt interact with the sleeve interior, while the block bears less direct attack from friction and gas exposure. Replacing or honing a worn sleeve is a conventional and comparatively economical rebuild step for engines that see high mileage or heavy duty use. In sleeveless engines, wear directly degrades the bore surface. If the coating flattens, cracks, or delaminates, the engine may require re boring or recoating, procedures that are more specialized and can be more costly than swapping a sleeve. The interplay of lubrication, ring seal integrity, and bore durability becomes central to reliability. In practice, engines designed for harsh environments often retain sleeved cylinders to maximize service life and ease of maintenance. In lighter, more efficiency driven passenger car concepts, sleeveless designs become attractive by shaving weight, reducing moving parts, and simplifying manufacturing, provided the coatings and materials can sustain the expected life cycle.

The story of wear and heat also includes a deeper look at manufacturability and lifecycle economics. Sleeve based designs require precise casting or insertion tolerances for the liner within the block, reliable sealing with O rings or gaskets, and careful assembly to avoid misalignment between the liner and piston. The advantage is modularity: sleeves can be replaced or re-sleeved when performance degrades. Sleeveless engines, while simpler in terms of components, demand rigorous surface engineering and material selection during casting and finishing. The bore must stay true to size, smooth to the touch, and resilient to micro wear and corrosion. In practice, OEMs weigh the cost of advanced coatings and rich manufacturing tolerances against the long term maintenance profile of the engine. A heavy duty or high performance engine will often favor sleeves because of their proven serviceability and the ability to refresh wear surfaces without a complete block overhaul. A compact, fuel efficient family car may lean toward sleeveless bores to reduce weight and cost, relying on surface technology to deliver the necessary durability. The decision, ultimately, is a balancing act among wear resistance, heat transfer, reliability, weight, and total cost of ownership across the engine life.

From a broader perspective, the presence or absence of sleeves becomes a reflection of an engine life story. A modern high efficiency four stroke engine tuned for low emissions may exploit a sleeveless architecture to shave weight and improve response, using advanced coatings to sustain life at modest to medium loads. A rugged diesel meant for long haul work or heavy duty equipment will often retain wet or dry sleeves because the ability to swap a worn liner is a practical insurance policy against costly block level repairs. The engineering conclusion is thus not about one path being universally superior, but about matching bore design to the engine mission. The same principle guides maintenance culture: some workshops prize the ease of sleeve replacement, while others invest in coating diagnostics, bore profile monitoring, and precision reboring capabilities for sleeveless designs. Each choice shapes the engine lifetime, its failure modes, and the ease with which technicians diagnose and fix problems when they arise.

As a reader seeking a concise primer, you can explore a focused resource that outlines the basics of engine sleeves and their roles. For a primer on what sleeves are and how they function, see What are engine sleeves? This succinct guide helps connect the broader themes of wear, heat transfer, and reliability to the concrete parts you may encounter in engine discussions. The linked resource complements the narrative here by anchoring the discussion in the practicalities of liner materials, installation tolerances, and typical maintenance workflows.

Ultimately, the question remains: do all engines have cylinder sleeves? No. The landscape is diverse, and the choice is driven by application, materials, and manufacturing philosophy. Sleeves offer a durable, serviceable path in demanding conditions, while sleeveless designs push toward lighter weight, simpler assemblies, and advanced surface engineering for efficiency. The right solution balances wear resistance with heat management, reliability with maintainability, and cost with performance. In practical terms, engines built for heavy duty use will still lean on cylinder sleeves for longevity and ease of overhaul. Engines designed for efficiency and weight savings in the passenger car segment often favor sleeveless bores, relying on coatings and precision casting to maintain performance and durability. The result is a spectrum rather than a dichotomy, with each design choice contributing to the engine’s ultimate behavior in the real world.

null

null

Final thoughts

Cylinder sleeve design is not a universal constant in engines; it is a design choice rooted in application, materials, and lifecycle goals. Sleeved engines excel in wear resistance, bore repairability, and proven durability in heavy-duty or cost-sensitive contexts. Sleeveless designs reduce weight, improve heat dissipation, and simplify assembly in some modern blocks, but demand precise manufacturing and robust surface treatments. For motorcycle and auto owners, understanding whether your engine uses sleeves helps explain parts availability, maintenance intervals, and repair options. For distributors and shops, sleeve strategies influence sourcing, warranties, and technician training. Regional manufacturing ecosystems and environmental standards further shape sleeve adoption, now and into the future. Expect a spectrum of solutions—from traditional sleeves to integrated or sleeve-in-block designs—as engines pursue higher efficiency, longer life, and targeted reliability within their specific market segments. The overarching message is practical: know the sleeve design of your engine to navigate parts, service, and cost with confidence.