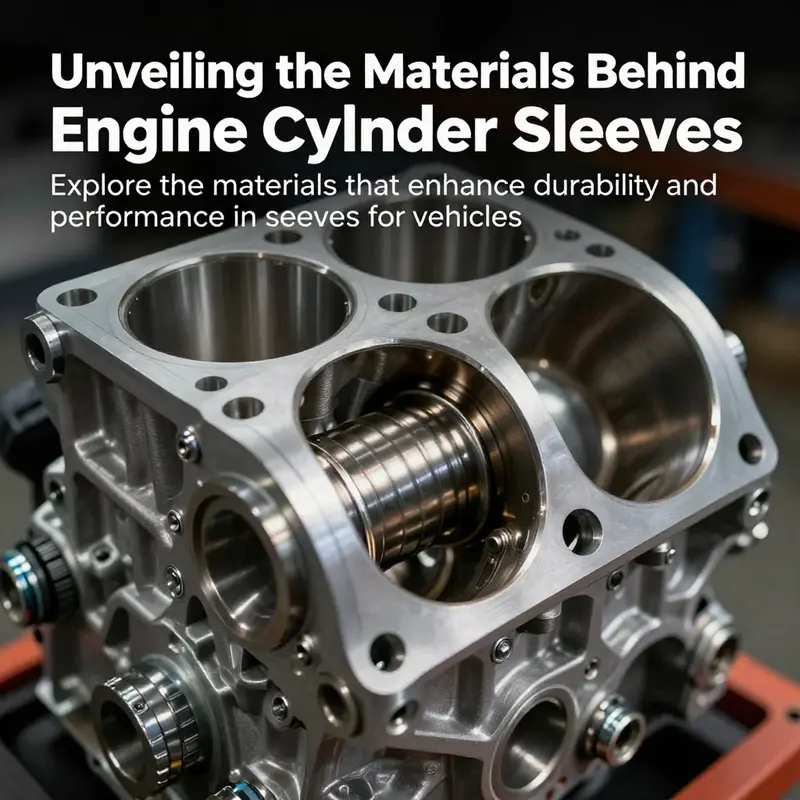

Understanding the materials used in engine cylinder sleeves is crucial for motorcycle and auto owners, auto parts distributors, and repair shops. The longevity and performance of an engine hinge on the quality of its components, and the choice of cylinder sleeve material is pivotal. High wear resistance, heat resistance, and corrosion resistance are some of the critical features these materials must possess. This article will delve deep into the prevalent materials found in engine cylinder sleeves, comparing their advantages and disadvantages, and exploring the innovative trends that may shape the future of these essential components.

Walls That Endure: Material Choices and the Quiet Engineering of Cylinder Sleeves

Cylinder sleeves are poised between harsh reality and careful engineering. They must resist abrasive wear, withstand intense heat, keep lubricants where they belong, and endure the repeated thermal and mechanical cycles of thousands of combustion events. The material chosen for these sleeves is not a mere detail; it governs long-term durability, service intervals, repair costs, and ultimately the engine’s efficiency and reliability. The decision process is a study in compromises: hardness versus toughness, heat transfer versus weight, machinability versus corrosion resistance, and cost against longevity. In this light, the materials most commonly employed—high-grade cast iron, steel alloys, and, more selectively, aluminum and exotic alternatives—reveal a spectrum of design philosophies that align with different engine architectures and operating regimes. To understand the core reasoning behind sleeve material selection, it helps to start with the workhorse of the industry: high-grade cast iron. Cast iron, in its refined forms, has earned its place through decades of steady performance in automotive and industrial engines. Its wear resistance arises from a hard, stable matrix that can bear the frictional onslaught of piston rings and lubricants. In addition, cast iron demonstrates robust thermal stability. Engines experience rapid temperature swings, and a material that can resist thermal fatigue while maintaining dimensional stability is invaluable. The graphite present in gray cast iron, and the spheroidal graphite in nodular cast iron, contributes not only to damping vibration but also to a degree of lubricity within the bore. This microstructural feature helps accommodate the micro-roughness that inevitably occurs as sleeves wear, reducing the initiation of scoring under heavy loading. In practice, high-grade cast iron sleeves often exhibit a water jacket surrounding the outer surface, allowing coolant to flow directly against the sleeve for efficient heat removal. This design enables the sleeve to stay within a narrower temperature band even when the engine is under peak load. The combination of wear resistance, thermal stability, and reliable lubrication compatibility makes gray and nodular irons the default choice for many engines, including those designed for diesel duty or demanding high-performance tasks. From a design perspective, the material’s compatibility with typical lubrication systems is a practical boon. The lubricant acts not only as a barrier to wear but as a vehicle that carries away heat and contaminants. Cast iron’s compatibility with such lubricants is well established, which reduces the risk of corrosive or abrasive interactions that could accelerate bore degradation. A typical sleeve configuration features a bore finish suitable for straightness and roundness, with the outer surface forming the interface with the block and water jacket. When engineers examine failure modes, they often cite two paths: surface wear and thermal distress. Cast iron’s microstructure lends resilience in both areas. Yet it is also prudent to acknowledge the limits: cast iron, while durable, is relatively heavy and can be less forgiving in very high-temperature cycles or when the engine architecture pushes thermal load beyond what a conventional sleeve can calmly shed. This has driven interest in alternative materials that can deliver lighter weight and improved heat transfer without sacrificing wear resistance or machinability. Aluminum alloys, for instance, have emerged as a preferred choice for modern gasoline engines seeking weight reduction and enhanced heat conduction. The appeal of aluminum sleeves rests on several coupled advantages. First, the reduced density translates to lower overall engine weight, which improves efficiency and responsiveness. Second, aluminum’s superior thermal conductivity helps in quick heat removal from the bore region, contributing to steadier operating temperatures and better control of thermal expansion. In long-run terms, better heat management limits the risk of hot spots that could accelerate wear or lead to piston ring glazing. But aluminum sleeves are not a universal panacea. The aluminum matrix presents different wear characteristics than cast iron, and the surface must be engineered to resist scuffing and micro-wear from the piston rings. Therefore, aluminum sleeves are often complemented by protective coatings or surface treatments, and their use is typically aligned with engines designed to exploit the weight savings and thermal advantages without compromising durability in high-load scenarios. As with any material choice, integration with the lubrication system remains central. Lubricants must effectively separate metal surfaces, control lubrication film stability, and shelter the bore from corrosive elements. Aluminum, when paired with the right alloy and surface finishing, can deliver robust performance in this milieu, particularly where the cooling circuit is tuned to keep the sleeve within an optimal temperature window. A question that frequently arises is whether there are niche materials that push the boundaries of conventional tradeoffs. Dry cylinder sleeves and wet cylinder sleeves represent divergent philosophies about heat transfer paths and maintenance implications. In dry sleeve designs, the sleeve is press-fitted into the engine block and does not rely on direct coolant contact around the sleeve’s outer surface. Heat transfer then largely proceeds through metal-to-metal contact with the surrounding block, and the sleeve itself may not be actively cooled by the coolant flowing near the outer surface. The practical upshot is a reduced risk of coolant leakage around the sleeve region and a simpler seal configuration in some block designs. However, this approach places greater emphasis on the sleeve’s own thermal mass and conductivity and demands precise fitment to avoid micro-movements that could degrade the bore. Conversely, wet sleeves sit within a cast portion of the block that forms part of the cooling system. They are cooled via the surrounding coolant, which interfaces with the sleeve’s exterior—or, depending on the design, via cooling channels embedded in the block around the sleeve, delivering heat away directly from the bore. The wet sleeve philosophy prioritizes heat removal and thermal uniformity, an advantage for engines operating under sustained high temperatures or high combustible loads. The result is a bore area that can be maintained at a lower average temperature, reducing the risk of thermal distortion during heavy-duty operation. Yet the wet-sleeve approach is not without its own complexities. The compatibility of the sleeve material with the cooling medium, the risk of coolant leakage around the joint, and the need for dependable sealing across many cycles of expansion and contraction all become essential engineering considerations. In many modern engines, the choice between a dry and a wet sleeve is not a mere preference but a holistic decision that reflects the block geometry, the intended service life, and the engine’s expected duty cycle. Beyond the mainstream materials of cast iron and aluminum, steel sleeves play a more specialized role in demanding environments. High-strength steel alloys—such as those formulated to resist deformation and to sustain heat dissipation under extreme loads—are used in turbocharged or high-compression engines where the mechanical demands on the bore are acute. The appeal of steel lies in its structural integrity and toughness, which can translate into longer wear life under aggressive conditions. The tradeoffs, however, include higher manufacturing costs, colder machinability, and the need for precise fits that align with the block’s tolerances and the engine’s dynamic behavior. When steel sleeves are adopted, designers typically rely on advanced heat-treating and finishing processes to sculpt a bore that can resist micro-engraving and scuffing while preserving the necessary surface texture for oil retention and boundary lubrication. In such contexts, a hardened steel sleeve can be more forgiving of piston ring pressure spikes and rapid accelerations. The discussion would be incomplete without acknowledging exotic and specialized materials that occupy narrower market segments. Ceramic sleeves, for example, offer exceptionally high wear resistance and very low friction coefficients. In theory, ceramics could dramatically extend bore life in engines exposed to extreme wear or demanding temperatures. In practice, ceramics come with significant manufacturing challenges and repair limitations. They require sophisticated production techniques, careful thermal management, and, importantly, they complicate repair strategies should bore damage occur. The same is true for copper alloys that may provide a lower coefficient of friction and favorable sliding properties under certain lubricants. These options are typically reserved for very high-end, low-volume applications where the performance benefits justify the cost and installation complexity. In all cases, the sleeve material choice must align with the engine’s overall design language, including bore geometry, journal alignment, cam profile, and the intended service environment. It is not enough to select a material on wear resistance and heat management alone; the sleeve must integrate with the block’s cooling system, facilitate reliable lubrication, and accommodate the machining tolerances required for a precise, repeatable bore finish. The outer surface, whether cooled by a water jacket or isolated by a dry-fit configuration, must be engineered to provide predictable heat transfer characteristics. In cast-iron sleeves, for example, the water jacket surrounding the sleeve’s exterior is designed to maximize heat extraction. This arrangement helps prevent hot spots that would accelerate bore wear or cause oil film breakdown. In aluminum sleeves, designers emphasize rapid heat removal while controlling expansion behavior to maintain bore roundness. The balance between thermal expansion and piston ring seating is delicate, and the sleeve’s material choice is central to achieving a consistent seal over the engine’s life. For readers who want a concise definition of these components and their role in the engine’s lifecycle, see What are engine sleeves?. This reference points to the fundamental concept that sleeves are more than mere liners; they are integral elements that determine heat management, lubrication behavior, and wear pathways in the bore. As the engine design community continues to push for greater efficiency, the material science of sleeves remains a fertile ground for innovation. Lightweight aluminum sleeves paired with advanced surface coatings, durable but lighter cast irons with refined microstructures, and high-strength steels able to survive extreme duty cycles each represent rational strategies for different mission profiles. Even within the same engine family, designers may tailor sleeve selection to optimize for fuel economy, durability, or weight reduction without compromising reliability. The emerging landscape also considers how sleeve materials interact with contemporary lubrication regimes and fuel formulations. Modern fuels, roughened bore surfaces due to long service intervals, and advanced coatings all interact with the base metal, influencing wear rates and the formation of protective tribofilms under boundary lubrication. In this regard, the sleeve’s surface finish is not simply a manufacturing afterthought but a critical design parameter that governs friction, heat transfer, and the initiation of wear tracks. The choice of material also implicates repairability and maintenance. Cast-iron sleeves, with their established track record, tend to be more forgiving in on-site repairs, particularly in engines designed around a robust lubrication strategy and predictable heat removal. Aluminum sleeves, albeit lighter and thermally efficient, may demand more careful inspection and specialized repair procedures, given the alloy’s particular vulnerabilities to certain stresses, such as galling and high-temperature oxidation in uncooled zones. Steel sleeves, while offering strong resilience, require exacting machining and alignment to achieve the intended fit and to sustain sealing through repeated thermal cycles. In addition to material properties, the sleeve’s interior bore surface finish—the texture and roughness that interact directly with piston rings—is a decisive factor in wear behavior. A well-honed finish supports stable oil films and reduces the risk of scuffing during cold starts or rapid accelerations. The durability of the enamel-like surface on a sleeve, whether smooth or textured, helps govern how quickly lubricating oil can form a protective film as piston rings seek a good seal against blowby. To understand the broader framework of sleeve materials and their interplay with engine design, this narrative keeps returning to the core principle: the sleeve is a mediator between the combustion process and the engine’s thermal and mechanical realities. It must absorb heat, sustain boundary lubrication, and resist wear in a highly dynamic environment. The material selection sits at the heart of that mediation, deciding how well the engine will perform over its intended life. It is no accident that different engine families converge on different material strategies. Where rugged, long-life duty takes precedence, cast iron remains a natural choice; where weight and heat transfer dominate, aluminum sleeves offer alluring benefits; for extreme mechanical demands, steel alloys provide a valuable, if more complex, alternative. And in the most specialized applications, ceramics or copper alloys may enter the conversation, offering marginal gains at a substantial premium. The result is not a single universal solution but a spectrum of informed choices. Each option comes with a matrix of costs and benefits, and the final selection reflects how an engine’s operating envelope—temperature, load, lubrication quality, duty cycle, maintenance regime, and footprint constraints—maps onto material behavior. In practice, engineers often rely on established data and standards to guide these decisions, while also permitting room for experimentation where the operating envelope justifies it. For those who wish to explore standards and technical specifications further, authoritative resources provide a foundation for understanding the rigorous testing and performance criteria that sleeves must meet under real-world conditions. External technical references, particularly those from SAE International, offer a structured window into the evolving expectation of materials, coatings, and design practices that govern cylinder sleeves in today’s engines. As this chapter has illustrated, the material used in engine cylinder sleeves is a central lever in achieving durability, efficiency, and reliability. The choice is rarely about a single property but about a balanced, context-specific compromise. It is a testament to engineering that a relatively small, often overlooked component—sitting between piston and block—can wield such influence over the engine’s practical life. The next chapters will expand on how these material choices interact with manufacturing methods, surface finishing technologies, and retrofitting considerations when sleeves wear or block damage occurs. In the meantime, the reader can appreciate that the modern engine rests on a delicate alloy of science, manufacturing precision, and strategic compromises that begin with the humble cylinder sleeve and the material that underpins its endurance. For readers seeking further context on the broader landscape of sleeve design—its history, common failure modes, and repair pathways—there is a rich body of work that continues to illuminate how materials science translates into reliable, real-world performance. And with ongoing advances in coatings, heat treatment, and microstructural engineering, the sleeve remains a dynamic focal point where durability, efficiency, and innovation converge. For readers who want to deepen their understanding of the standards and technical criteria that shape these choices, the SAE International literature provides a rigorous framework for assessing material performance, thermal management, and wear resistance under realistic engine conditions. (External reference: https://www.sae.org)

Sleeve Materials That Make Engines Last: Weighing Cast Iron, Aluminum, Steel and Advanced Options

Engine cylinder sleeves are small components with oversized responsibilities. They define the running surface for piston rings, control heat flow in and out of combustion chambers, and set the foundation for long-term wear resistance. Choosing sleeve material is not a single-criteria decision. Engineers balance thermal behavior, wear properties, manufacturability, cost, repairability, and compatibility with engine block architecture. This chapter walks through those trade-offs in an integrated narrative so you can see why cast iron remains common, when aluminum alloys make sense, and where steel and advanced ceramics find their roles.

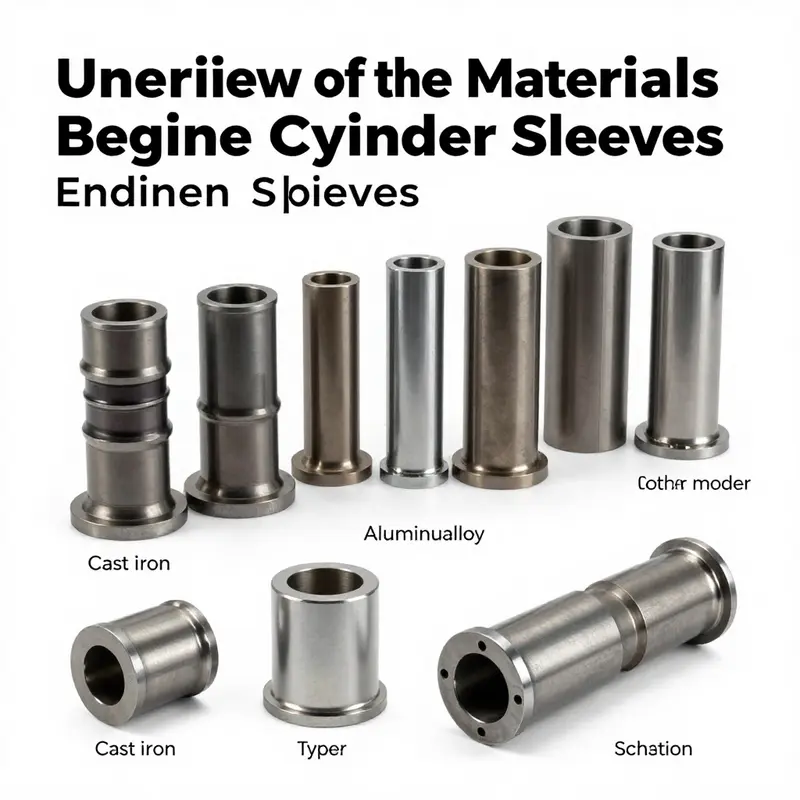

A sleeve’s job is deceptively simple: provide a hard, stable bore that resists wear while transferring heat away from the combustion area. But the demands on that surface vary wildly. Heavy-duty diesel engines see high combustion pressures and long duty cycles. High-revving gasoline engines prioritize low friction and rapid heat rejection. Compact engines require thin walls and tight weight budgets. Across these use cases, three material families dominate: cast iron, aluminum-based systems, and high-strength steels. Emerging solutions add ceramics or copper alloys for niche gains. Each option changes how heat, load, and lubrication behave at the critical ring-to-bore interface.

Cast iron became the default because it answers many questions at once. Its carbon-rich matrix yields excellent wear resistance and inherent lubricity thanks to graphite structures. That graphite scatters heat and supplies tiny reservoirs of lubricant at the surface, helping piston rings glide with less aggressive surface finishing. Cast iron also offers robust thermal conductivity compared with many steels; that helps move combustion heat into the block and then into the cooling system. For engines built around durability and low per-unit cost, cast iron sleeves deliver proven longevity and forgiving service characteristics.

There are important nuances in cast iron choices. Gray cast iron contains flake graphite and typically provides the best vibration damping and oil retention. Ductile, or nodular, cast iron forms spherical graphite nodules. Those nodules give better tensile strength and resistance to impact and thermal shock. Alloyed variants add elements like chromium or molybdenum to boost hardness and wear resistance further. In practice, cast iron sleeves are used extensively in commercial diesel engines and large-displacement petrol engines because they tolerate heavy loads and are easy to recondition. The trade-off is mass: cast iron sleeves add weight that reduces the power-to-weight ratio and can slow transient thermal response in lightweight engine designs.

Aluminum alloy sleeves represent a different philosophy. Instead of relying on a heavy, hard matrix, they aim for low mass and excellent heat transfer. Aluminum-silicon alloys are common because silicon improves wear resistance and dimensional stability at elevated temperatures. Alone, bare aluminum is too soft for a piston ring to run directly on, so manufacturers pair aluminum with harder surface solutions. These include plasma-sprayed ceramic coatings, thin hard liners, or diffusion-bonded overlays. The result is a lightweight sleeve package that pulls heat away from the combustion space faster than iron. Faster heat transfer can lower peak temperatures and reduce detonation risk, which benefits high-revving gasoline engines.

The advantages of aluminum-based systems are clear in applications that prize efficiency and quick thermal response. Reduced reciprocating mass improves throttle response and allows lighter engine blocks. Coated aluminum surfaces can achieve very low friction, improving emissions and fuel economy in modern engines. However, these gains come with added manufacturing complexity. Coatings must bond perfectly and resist micro-cracking under thermal cycling. If the protective layer fails, the underlying aluminum can corrode or gall. Aluminum sleeves also risk galvanic corrosion if the sleeve contacts dissimilar metals in a wet environment. That means careful material pairing, insulation, and corrosion control become part of the design process.

High-strength steel sleeves carve out their niche where mechanical load and thin-wall rigidity matter most. Alloy steels, often through heat treatment and surface engineering, bring exceptional tensile strength and fatigue resistance. They hold tight tolerances under heavy loading and resist deformation during prolonged service. Steel sleeves work well in turbocharged engines, industrial diesels, and marine applications where structural integrity under high pressure cycles is non-negotiable. Because steel is less thermally conductive than cast iron or aluminum, its use typically occurs in engines with aggressive cooling strategies or where the surrounding block can manage heat removal.

Steel sleeves have drawbacks. Their lower thermal conductivity can raise localized temperatures unless the cooling system is designed to compensate. Machining and finishing steel to the required surface quality for piston rings is more expensive than working cast iron. Without proper surface treatment, steel is prone to galling, where adhesive wear causes material transfer between ring and sleeve. To avoid this, steel sleeves often receive wear-resistant coatings or nitrided surfaces. The result is higher manufacturing and refurbishment cost, offset by superior structural performance.

Beyond these three mainstream families, specialty materials and surface systems extend possibilities. Ceramic sleeves or ceramic-coated bores achieve extremely high hardness and low friction, dramatically increasing wear resistance. Ceramic is attractive for racing applications where component life is sacrificed for peak performance, or in engines designed to run with minimal lubrication. The catch is cost and brittleness: ceramics resist abrasion but do not tolerate impact or sudden temperature changes as well as metal. If a ceramic surface cracks, repair is difficult and often impractical.

Copper alloys and bronze liners appear in applications that emphasize friction reduction and thermal transfer in specific contexts. These alloys can offer low coefficients of friction and high thermal conductivity. They are rare because the material cost is high, and machining and joining strategies become complex. Where copper alloys perform best is in highly specialized or low-volume engines, or as part of a composite liner where a thin copper layer is combined with a supporting substrate.

Material choice cannot be separated from sleeve architecture. Dry sleeves sit within the engine block and do not contact coolant directly. They must conduct heat into the block efficiently and maintain a precise interference fit. Because dry sleeves transfer heat through the surrounding metal, high thermal conductivity in the sleeve material benefits block temperature control. Wet sleeves, conversely, are exposed to coolant on their outer surface. They allow direct heat exchange with coolant and often simplify repair and replacement. Aluminum sleeves paired with wet designs can excel at thermal management. However, wet sleeves bring sealing challenges and higher demands on corrosion resistance, making material selection and surface protection critical.

Manufacturing and installation methods influence material suitability. Cast-in sleeves form part of a cast block, easing production for high-volume engines. Press-fit or shrink-fit sleeves allow replacement and reconditioning, favoring materials like cast iron and steel. Plasma-sprayed or electroplated coatings, applied after bore machining, enable aluminum blocks to receive a hard running surface without inserting a separate liner. Each approach has trade-offs in tolerances, long-term adhesion, and the ability to recondition the bore during overhaul.

Serviceability and repairability are practical factors that often drive choice as much as raw material properties. Cast iron sleeves are easy to machine and re-hone. Engine rebuilders can restore bores with established techniques. Aluminum sleeves with bonded coatings are harder to repair because the coating must be re-applied under controlled conditions. Steel sleeves, while robust, demand specialized equipment for re-boring and finishing. Life-cycle cost analysis typically shows cast iron has a lower total cost of ownership for fleet and heavy-duty applications because of simpler repair paths and lower initial material cost.

Thermal considerations also dictate design choices. Materials with high thermal conductivity reduce thermal gradients across the bore wall. Lower gradients reduce distortion, improving ring sealing and reducing blow-by. But if a sleeve conducts heat too quickly away from the combustion chamber without the block or cooling system managing it, cold spots can emerge and lead to condensation or uneven combustion. Designers balance conductivity against cooling architecture. Aluminum alloys pull heat rapidly, which benefits short transient bursts and high-revving engines. Cast iron smooths thermal swings and tolerates slow ramping more robustly.

Friction and lubrication behavior are equally important. A sleeve must work with piston rings and oil film thickness to maintain a hydrodynamic lubrication regime across the operating range. Graphite in cast iron helps maintain a stable oil film under many conditions. Ceramic coatings reduce friction but can alter oil retention and distribution. Engineers specify surface textures, cross-hatch patterns, and micro-finish values precisely to ensure reliable oil film formation. The right combination of surface roughness and material determines wear rates and oil consumption over time.

Corrosion resistance cannot be ignored, particularly for wet-sleeve designs. Aluminum alloys need careful isolation from dissimilar metals to prevent galvanic corrosion in coolant. Protective coatings, inhibitors in the cooling system, and proper sealing surfaces reduce risk. Steel sleeves require corrosion-resistant treatments or stainless variants if exposed to coolant. Cast iron resists many forms of corrosion but can develop pitting if coolant chemistry is poorly controlled.

Cost and supply-chain considerations shape real-world decisions. Cast iron remains attractive because foundry infrastructure is global and well understood. Aluminum processing and high-performance coatings incur higher per-unit cost and more complex supply chains. Steel sleeves often need heat treatment and specialized machining, which increases lead times and inventory cost. In volume production, small per-unit differences become substantial. OEMs choose materials that align with manufacturing capabilities, warranty strategies, and target markets.

Selecting a sleeve material is therefore an exercise in systems thinking. It begins with application requirements: expected load cycles, target service life, allowable weight, and thermal limits. It continues with manufacturing constraints, surface finishing capabilities, and maintenance scenarios. For a heavy-duty truck engine, cast iron or steel sleeves might be selected for structural durability and rebuildability. For a high-strung motorcycle or lightweight passenger engine, aluminum sleeves with robust ceramic coatings can deliver the thermal and friction benefits needed to hit performance targets.

The engineering process ultimately translates these considerations into specifications: acceptable wall thickness, interference fit, surface roughness, coating thickness, and inspection criteria. Material testing under representative loading and thermal cycles verifies choices. Tests focus on scuffing resistance, ring seal retention, heat transfer rates, and corrosion behavior. Designers also consider how the sleeve integrates with emissions control strategies, since friction and thermal efficiency influence fuel consumption and exhaust composition.

To understand the practical impacts, consider a comparison across common priorities. For wear resistance and simple reconditioning, cast iron scores highly. For weight-sensitive designs that need rapid heat rejection, aluminum with a well-bonded hard surface is preferable. For structural integrity in extreme loads, high-strength steels deliver the necessary strength. Advanced ceramics can beat all three in hardness and low friction but at a cost premium and with brittle failure modes that prohibit widespread use.

Finally, material choice must align with the chosen sleeve architecture—dry versus wet, cast-in versus inserted, and the block material itself. Aluminum blocks often receive sleeves differently than iron blocks. Coatings and liners must account for differences in thermal expansion and electrochemical potential. The right combination is a matched system, not a single material decision.

If you want a concise primer on what sleeves do and how they are classified, see this short explainer on what engine sleeves are. For manufacturer-specific technical guidance that explains selection and testing criteria for sleeve material choices, consult the technical sleeve guide provided by an engine manufacturer that details composition and performance targets: https://www.hino.com/en/technical/sleeve-guide-j05e

In practice, the best sleeve material is the one that meets the engine’s performance, durability, and economic objectives as part of a coordinated design. Material science and surface engineering continue to advance, giving designers more options. Still, the engineering trade-offs—heat management versus weight, hardness versus brittleness, ease of repair versus peak performance—remain the enduring drivers of sleeve selection.

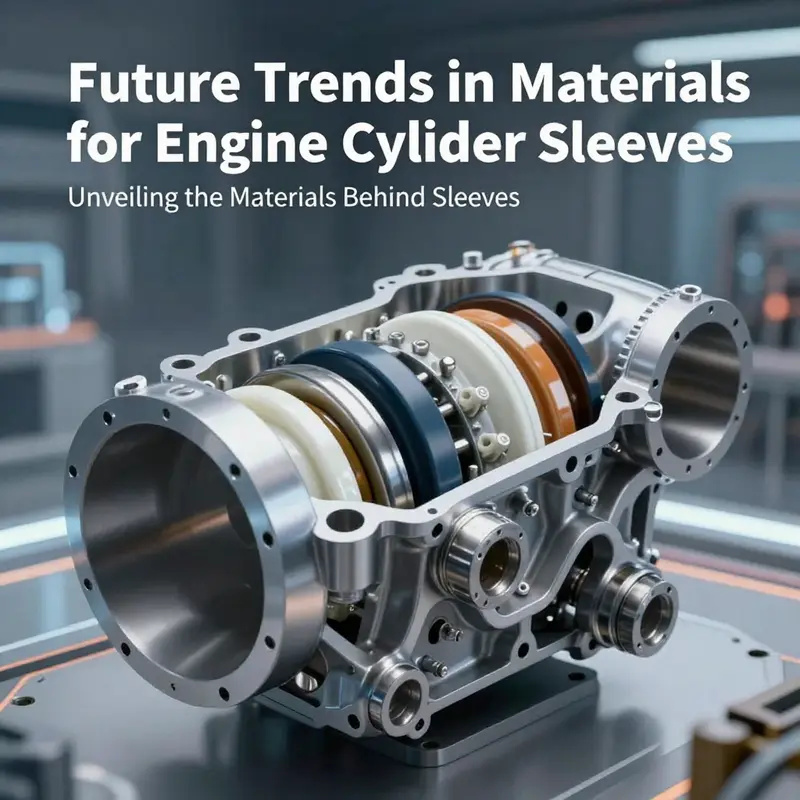

From Cast Iron to Composites: Future Materials and the Next Generation of Engine Cylinder Sleeves

Engine cylinder sleeves occupy a critical and often underappreciated role in internal combustion engines. They are the first line of defense against bore wear, a primary pathway for heat transfer from the combustion chamber to the cooling system, and a dynamic interface where oil films must simultaneously seal, lubricate, and protect. The sleeve material, its thickness, and the way it interacts with the piston rings, coolant, and lubricants ultimately shape engine durability, efficiency, and emissions. For decades the industry relied on a relatively narrow family of materials driven by rugged performance and predictable machinability. Cast iron has been the stalwart workhorse in many diesel and high load applications because it combines wear resistance with thermal stability and oil retention. Gray cast iron, with its graphite lamellae, dissipates heat effectively and cushions impact; nodular or ductile cast iron introduces additional toughness from graphite nodules that help absorb stress and resist cracking. Alloy cast irons push these properties further, tailoring hardness and microstructure to balance wear resistance with machinability. In gasoline engines, aluminum alloy sleeves have grown in popularity because they bring a vital advantage that is harder to achieve with iron — weight savings and improved heat transfer. A lighter sleeve reduces reciprocating mass and contributes to better transient response and fuel economy while enabling more aggressive cooling strategies. Yet aluminum sleeves also pose challenges in wear resistance and oil management, especially under high load and high rpm conditions where oil films must be carefully controlled to prevent galling and scuffing. The conventional picture also includes steel sleeves for certain high load and high performance scenarios, where high strength and good fatigue performance under aggressive operating conditions are required. Ceramic sleeves have emerged in some research contexts as a pathway to ultra low wear and reduced friction, but their practical adoption remains limited by cost, fabrication complexity, and repairability. Copper alloys offer low friction and good thermal conductivity but bring their own integration challenges, including material cost and compatibility with current lubrication regimes. Each material family brings a distinct balance of properties, and the choice is seldom driven by a single metric. It is a system decision that accounts for engine type, duty cycle, lubrication philosophy, and the available manufacturing ecosystem. A concise primer on the fundamentals of engine sleeves can be found here What are engine sleeves.

Final thoughts

The choice of material for engine cylinder sleeves significantly influences an engine’s performance and longevity. Cast iron and aluminum alloys dominate the market today, each with specific advantages suited to different applications. Materials such as steel and ceramics offer high performance but come with their challenges. As technology advances, we can expect the emergence of innovative materials that improve efficiency and reduce weight, enhancing the overall performance of engines. For motorcycle owners, auto enthusiasts, and repair professionals, a solid understanding of these materials is vital for making educated decisions regarding maintenance and upgrades.